Minimum Clinically Important Difference for Nonsurgical Interventions for Spinal Diseases: Choosing the Appropriate Values for an Integrative Medical Approach

Article information

Abstract

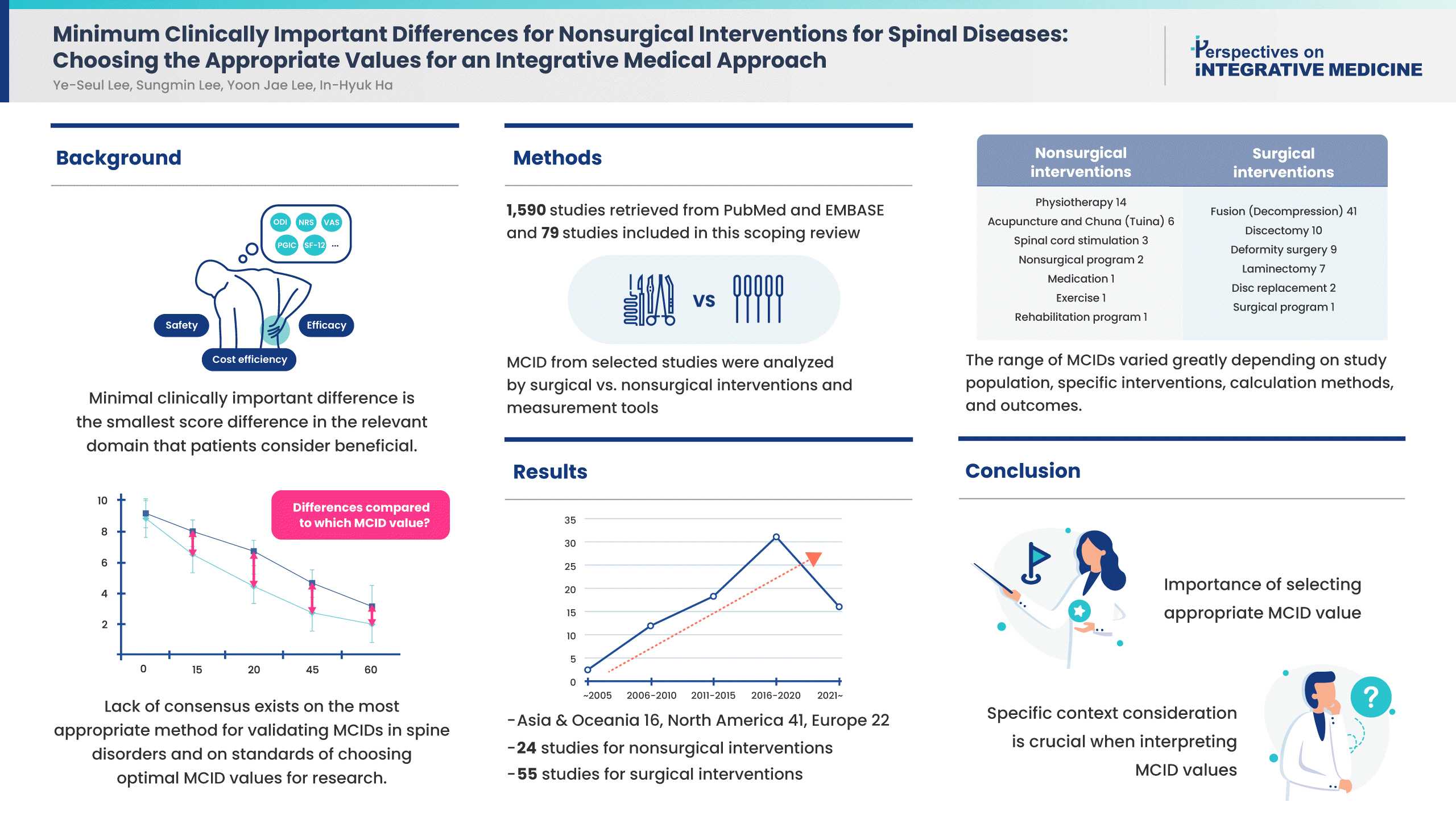

The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) plays a crucial role in the design and interpretation of clinical trials, as it helps in distinguishing between statistically significant and clinically meaningful outcomes. This scoping review aims to collate and appraise the current research concerning the validation of MCIDs for surgical and nonsurgical measures for spine disorders. Two databases of MEDLINE (PubMed and EMBASE) were searched. There were 1,590 studies retrieved and 79 were selected as eligible for review. Measurement tools such as the Oswestry Disability Index, Neck Disability Index, Numeric Rating Scale, and Visual Analogue Scale were assessed by regions and interventions. A total of 24 studies identified MCIDs on nonsurgical interventions, and 55 studies identified MCIDs on surgical interventions. The range of MCIDs varied greatly depending on study population, specific interventions, calculation methods, and outcomes. This scoping review emphasizes the complexity and variability in determining MCIDs for musculoskeletal or neurodegenerative spinal diseases, influenced by several factors including the intervention type, measurement tool, patient characteristics, and disease severity. Given the wide range of reported MCIDs, it is crucial to consider the specific context when interpreting these values in clinical and research settings. To select an appropriate MCID value for comparison in a clinical trial, careful consideration of the patient group, intervention, assessment tools, and primary outcomes is necessary to ensure that the chosen MCID aligns with the research question at hand.

Introduction

Minimal clinically important difference (MCID) is an extensively used tool in healthcare clinical trials, and is defined as “the smallest difference in score in the domain of interest which patients perceive as beneficial [1].” Reporting the results using MCIDs is easily interpretable and efficient, particularly in clinical trials employing patient reported outcomes. Due to its usefulness, a vast range of studies have utilized this concept since its introduction [2]. By providing a statistical measure to assess the effectiveness of clinical interventions, this concept is particularly relevant in the field of spine disorders, where both surgical and nonsurgical treatments are employed to alleviate pain and improve patient function, and where patient reported outcomes comprise a substantial portion of the outcomes. The evaluation and validation of MCIDs in these interventions are vital to ensure appropriate patient care, as well as to determine the effectiveness of new and existing treatments.

Surgical and nonsurgical treatments for spine disorders encompass a wide range of interventions. Surgical measures often include procedures such as spinal fusion, discectomy, laminectomy, and foraminotomy, among others. On the other hand, nonsurgical interventions may involve physical therapy, pain management (including medication and injections), lifestyle modifications, and complementary and alternative medicine approaches including acupuncture and Tuina (Chuna). The MCID values for these interventions can differ significantly, and the wide range of recommended MCID values for the same instrument [3,4] highlights the need for context-specific validation.

Determining the MCID is not a straightforward process, and various methods are employed to derive these values. Anchor-based approaches, distribution-based techniques, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis represent the most common methods used for MCID validation. Anchor-based approaches use an external criterion or “anchor” to interpret the meaning of a change in the outcome measure, whereas distribution-based methods relate the observed changes to the variability of the measure. ROC curve analysis provides an alternative method, utilizing sensitivity and specificity to assess the cut-off point that best differentiates between improvement and no improvement in patient symptoms.

Each of these methods carries inherent strengths and weaknesses, and their use often depends on the context and the nature of the intervention under study. However, there is currently no consensus on which method is the most appropriate or accurate for validating MCIDs in the context of spine disorders. Discrepancies between anchor-based and distribution-based MCIDs [5] have been reported, and the lack of agreement poses challenges for clinicians and researchers in the interpretion of clinical trial results and in making informed decisions about patient care.

The MCID plays a crucial role in the design and interpretation of clinical trials, as it helps in distinguishing between statistically significant and clinically meaningful outcomes. Without a proper MCID, the results of clinical trials can be misleading, and interventions that are statistically effective may not translate into meaningful improvements in patient outcomes. Differences in the range of MCIDs for the same disease have been observed by interventions [6], implying the need to review the related literature. An appropriately selected MCID can provide guidance in clinical decision-making by helping to quantify the benefits and harms of different interventions.

This scoping review aimed to address the existing knowledge gap by collating and critically appraising the current body of research concerning the validation of MCIDs for surgical and nonsurgical measures for spine disorders. It will provide a comprehensive overview of the current methods of MCID validation, highlight the most common surgical and nonsurgical measures, and underscore the importance of determining the most appropriate MCID in the context of clinical trials. In doing so, this review hopes to contribute to the ongoing discourse and pave the way for more robust and patient-centered approaches in the management of spine disorders.

Materials and Methods

This scoping review was designed to identify MCIDs for musculoskeletal disorders and neurodegenerative diseases of the spine. A scoping review is a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses exploratory research questions that try to map significant concepts, types of evidence, and research gaps pertaining to a given topic or field by finding, collecting, and synthesizing existing knowledge [7]. This study followed the method based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews [8] The following five steps were used to conduct this scoping review: (1) identification of the research question; (2) identification of relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting of data; and (5) collecting, summarizing, and reporting the results as described by Peters et al [9]. This study followed the method based on the Arksey and O’Malley framework [10].

1. Identifying the research questions

Prior to the initiation of this study, the broad research question was “what are the differences between MCIDs for nonsurgical interventions and those for surgical interventions in spinal diseases?” The more detailed research questions used after starting the study were as follows: (1) What is the difference in the reported MCID across various types of interventions (i.e., surgical and nonsurgical interventions) for spine disorders? (2) How do different methods of study design impact the reported MCID values for spine disorders? (3) Are there any cultural or geographical factors that may influence MCIDs? (4) What is the difference in the choice of patient-reported outcome measures across reported MCIDs in surgical and nonsurgical interventions for spine disorders? and (5) Considering the MCID values reported, how might the choice of treatment intervention and outcome measurement instruments influence the interpretation of clinical significance in studies of surgical and nonsurgical interventions for spine disorders?

2. Identifying the relevant studies

The initial search was conducted using the two electronic databases of MEDLINE, via PubMed and Excerpta Medical dataBASE (EMBASE). An example of the specific search strategy is listed in Table 1. Modifications to the search terms and search strategies were adopted in reference to the database being searched.

3. Study selection

3.1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

This study reviewed studies which assessed MCIDs for spinal diseases treated by surgical or nonsurgical interventions. Human studies including randomized controlled trials, controlled clinical trials, case series, case reports, pilot clinical studies, and retrospective observational studies were reviewed for eligibility. In vivo and in vitro experiments, reviews, duplicate articles, ongoing studies, and studies that failed to provide detailed results or with incomplete data were excluded. The language was restricted to English, and time period was restricted to studies published since 1989 when the concept of MCID was first introduced [1]. An elaborate search criteria is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Eligible participants were defined as patients with spinal disease who were: (1) over 18 years of age; (2) who were, or had been, going through treatment for musculoskeletal or neurodegenerative disorders in the neck or back; and (3) who received either surgical or nonsurgical interventions to address the symptoms. Patients experiencing other types of disorders such as tumor or autoimmune diseases such as ankylosing spondylitis were excluded from this scoping review. No restriction was applied according to sex, ethnicity, symptom severity, disease duration, clinical setting, and country of study.

Examples of surgical interventions in this study include discectomy, disc replacement, laminectomy, fusion, and/or decompression surgery. Examples of nonsurgical interventions in this study include physical therapy, exercise and education programs, spinal cord stimulation, and complementary and alternative medicine therapies such as acupuncture and Tuina (Chuna).

The outcomes collected and reviewed in this study were MCIDs across a number of assessment measurements, including the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Physical Function (PROMIS-PF), EuroQol 5-dimensions (EQ-5D), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) for different types of pain, and Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain.

3.2. Screening and agreement

The electronic databases were searched independently by two researchers using the search strategies described above and the retrieved studies were screened for eligibility. Upon the initial search, all citations were uploaded to EndNote X20 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). After removing the duplicates, full texts were reviewed in detail using the inclusion criteria. The number of results for each database search was noted and presented in a PRISMA flow diagram. The reasons for excluding studies were recorded for individual studies.

3.3. Charting the data

As this review focused on comparing the reported MCIDs and the methods used to validate the MCID, the study information assessed for this review were as follows: the 1st author, corresponding author, publication year, country, language, study type, patient disease, type of intervention(s), outcome measures, primary outcome, secondary outcome, reported MCIDs, and statistical analysis method. Data extraction was performed independently by two researchers and any differences were resolved through discussion. The data charting table was modified as necessary during the process of data extraction.

3.4. Collecting, summarizing, and reporting the results

After coding the included studies, the contents of the studies were analyzed. The extracted data were presented in tabular form in line with the objective of this scoping review. The distribution of the studies by the aforementioned extracted information was analyzed. A qualitative analysis was conducted to illustrate an overview of each study. The tabulated results were supported by narrative summaries to describe the results in relation to the objective of this scoping review.

Results

1. Literature search and selection

Based on the search strategy, a total of 1,590 studies published on MCIDs for spinal diseases were retrieved from PubMed and EMBASE. After title and abstract screening, a total of 604 studies were assessed for eligibility. After the assessment of full-text, a total of 489 studies were excluded for the following reasons: RCTs on the effectiveness of specific interventions (n = 331), studies on autoimmune diseases and/or metastatic diseases (n = 29), studies on risk factors for spine disease prognosis (n = 139), and instrument validation (n = 24). A total of 79 studies were included for this scoping review. The PRISMA flow chart was used to track the number of articles at each stage of the review (Fig. 1).

2. General characteristics of the identified literature

A total of 79 studies were reviewed in this study (Supplementary Table 2). They were conducted between 2004 and 2022, and the number of studies showed an increasing trend over the years (Fig. 2). The largest number of studies (10 articles) were published in 2019. Research was conducted in various regions including the USA, Japan, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, Thailand, Belgium, Turkey, Canada, Iran, the Republic of Korea, Denmark, Spain, and China. Multiple study designs were present, but most of them were based on observational study designs including retrospective or prospective cohort studies. Other study designs included a case-control study and secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial.

Number of related studies over time since the introduction of the minimal clinically important difference in 1989.

MCIDs for nonsurgical interventions using various assessment tools or instruments were identified in 24 studies (Table 2). The interventions assessed in these studies were diverse, encompassing physical therapy, pain medication, exercise and education programs, spinal cord stimulation, acupuncture, Chuna (Tuina), cupping, and other rehabilitation programs. A wide array of instruments have been used across these studies to measure treatment outcomes, and commonly used tools include PROMIS-29, neck disability index (NDI), SF-12, NPS, and ODI.

MCIDs for surgical interventions using various assessment tools or instruments were identified in 55 studies (Supplementary Table 3). Spinal conditions included spinal conditions in the neck and back, including degenerative cervical myelopathy, cervical radiculopathy, lumbar spinal stenosis, and lumbar degenerative disc disease, among others. Interventions encompassed discectomy, disc replacement, laminectomy, and fusion and decompression surgery.

Instruments used to measure outcomes included ODI, PROMIS-PF, Japanese Orthopaedic Association score, NRS and VAS for various types of pain, health-related quality of life assessment measurements such as Short Form (SF)-36 survey, and EQ-5D, and tests such as the timed-up-and-go (TUG) test, and 6-minute walk distance. MCIDs for some instruments, e.g., PROMIS, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia was determined only for nonsurgical treatments. On the other hand, MCIDs for certain instruments such JOABPEQ was determined only for surgical treatments.

Anchor-based, distribution-based, ROC analysis, or a combination approach were used to determine the MCIDs. The reported MCID values varied significantly across the studies, interventions, and instruments used. For example, the MCID for the TUG test conducted by Maldaner et al in 2022 [11] on patients who had gone through lumbar disc surgery was 2.1 seconds. In contrast, the MCID for the TUG test conducted by Gautschi et al [12] in 2017 on patients who had gone through microdiscectomy was 3.4 seconds. Similarly, the MCID for the ODI ranged from 9 [13] to above 26.6 [14].

3. Reported MCIDs by instruments and by interventions

When MCIDs of the ODI were assessed by interventions (Table 3), MCIDs across nonsurgical interventions, reported in eight studies [5,13,15–18], ranged between 2.23–14.31 [15] on pain medication. Studies which calculated a single value ranged from 2.45 [19] on a composite of nonsurgical procedures for adult spine deformity and 9 [13] on acupuncture and Chuna (Tuina) for failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS), or a minimum of 50% change for physical therapy using the ODI [20]. MCIDs across surgical interventions for the back, reported in 20 studies [14,15,19,21–37], ranged from 0.17 [30] on fusion surgery to 27 [37] on discectomy, or a minimum of 42.4% change for decompression surgery [22].

MCIDs for the NDI were assessed by interventions (Table 4). MCIDs across nonsurgical interventions, reported in ten studies [5,38–45], and ranged from 1.66 [45] for physiotherapy with manual therapy techniques to 18 [5] on a composite of nonsurgical treatment for spine disorders. The change in the NDI for physical training ranged from 20% to 60%. MCIDs across surgical interventions on the neck, reported 20–60% in 8 studies [46–53], ranged from 2.72–12.08 [51]. When assessing symptom change, one study on physical training reported 20–60% change in the NDI [40] while studies on discectomy and fusion surgery reported a 16% [46] to 30% [47] improvement for degenerative cervical diseases.

MCIDs for the NRS and VAS were assessed by interventions and by regions (Supplementary Table 4). Five studies [38,39,42–44] reporting NRS/VAS scores for neck pain from nonsurgical treatments ranged from 1.3 [43] to 2.5 [38,44] in NRS. One study on nonsurgical interventions for the neck reported NRS scores for arm pain with an MCID of 1.5 [54]. Five studies reporting NRS/VAS scores for back pain from nonsurgical treatments ranged from improvements in scores of between 1.2 to 3.7 in the VAS [17], and from 0.9 [16] to 4 [18] in the NRS. Seven [46,47,49,52,53,55,56] studies reporting NRS/VAS scores for neck pain from surgical treatments ranged from as low as 0.36 [56] to 2.6 [52] in the VAS. Symptom change ranged from 16% [46] to 30%[47]. Five [47,49,52,53,55] studies reporting NRS/VAS scores for arm pain from surgical treatments ranged from 1.3 [49] to 4.1 [52], and a minimum of 30% change in symptom [47]. Nineteen studies reporting NRS/VAS scores for back pain ranged from 0.02 [30] to 4.2 [14] in the NRS, and 1.16 [31] to 6.5 [33] in the VAS. The NRS score change for back pain ranged from 25% [22] to 33% [27]. Fourteen studies [14,22,23,27–33,35,36,57,58] reported MCIDs for leg pain from surgical treatments for the back, ranging from 0.02 [30] to 3.5 [29,57] in NRS scores, with changes ranging from 40% [27] to 55.60% [22]. Lastly, two studies reported MCIDs for NRS scores for leg numbness, ranging from 2 [57] to 3.75 [22].

Discussion

This comprehensive scoping review of 79 studies, spanning 18 years of research, provides an in-depth evaluation of the available literature on the MCID for both non-surgical and surgical interventions in spinal diseases. The studies were conducted across a broad geographical range, indicating a global interest in this topic. The findings highlight the complexity of determining the MCID, with a broad range of values reported across different studies, interventions, calculation methods, measurement tools, and patient populations.

Notably, the use of numerous assessment tools across studies suggests that there is no consensus on a standardized tool for measuring treatment outcomes in spinal diseases. This variety of instruments used across studies may contribute to the significant variation in the MCID values reported. PROMIS-29 [5,49,59–61], NDI [5,11–14,16,19,20,22–32,35,36,38–54,56,58,61–78], SF-12 and SF-36 [13,19,22,30–36,42,49–53,56,57,60,62,69,72,78–80], NRS [14,16,18,22,25,27,29,43,44,46,47,54,57,64], and ODI [5,12–27,29–37,42,47,48,52,59,60,66,70,71,74,81,82] were common assessment tools, but their application varied, indicating that the choice of instrument may be context-specific. Some tools like PROMIS [5,49,59–61], the Beck?Depression Inventory [16,17], and the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia [83] were only used for non-surgical treatments, while others [58,70] were specific to surgical treatments. This suggests further research is needed to establish the suitability of specific tools for different interventions and conditions.

The methods used to calculate the MCID, including anchor-based, distribution-based, and ROC analysis, or a combination thereof, varied across studies. The diverse methodologies employed may also contribute to the variability in reported MCID values. The difference in MCID values for the same measurement tool, for example, the TUG test [11,12,41], emphasizes the influence of the study population and the specific intervention on the MCID.

A wide range of MCIDs were observed in this study, even within the same intervention. For example, the MCID for the ODI across non-surgical interventions ranged from 2.23 to 14.31 in relation to pain medication, and from 0.17 to 27 for surgical interventions like fusion surgery, and discectomy. This variability reflects the influence of specific patient characteristics, disease severity, and intervention specifics, further indicating that the MCID is highly context-dependent.

The same variability was seen in MCIDs for the NDI across interventions, where values ranged from 1.66 on physiotherapy with manual therapy techniques, to 18 on a composite of non-surgical treatment for spine disorders. Regarding pain assessments, a wide range of MCID values for the NRS and VAS were reported. The values ranged from as low as 0.02 to as high as 4.2 for back pain following surgical interventions. This suggests a potential influence of the type and combination of treatments on the MCID, further underscoring the variability in MCIDs depending on the specific intervention and patient population.

In conclusion, this scoping review highlights the growing body of research on MCIDs over time across various spinal diseases. The result emphasizes the complexity and variability in determining MCIDs for spinal diseases, which are influenced by several factors including the type of intervention, measurement tools, patient characteristics, and disease severity. Given the wide range of reported MCIDs, it is crucial to consider the specific context when interpreting these values in clinical and research settings. This study points to the importance of selecting the most appropriate value of MCID in clinical research as well as in clinical practice of spinal diseases. To select an appropriate MCID value for comparison in a clinical trial, careful consideration of the patient group, intervention, assessment tools, and primary outcomes is necessary to ensure that the chosen MCID aligns with the research question at hand. The findings also underscore the need for further research to understand the influences driving these variations when determining MCIDs. Further effort would be beneficial for both clinical decision-making, and for the design and interpretation of research studies in this field.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at doi:https://doi.org/10.56986/pim.2023.06.003.

Notes

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: YSL. Formal analysis: SL and YSL. Methodology: YJL. Project administration: IHH. Writing original draft: YSL. Writing-reveiw and editing: YJL.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement

This research is literature review that does not require IRB approval.

Funding

This research article did not receive any financial funding.

Data Availability

All relevant data are included in this manuscript.