Current Status of Korean Medicine Treatment for Post-acute COVID-19 Syndrome: A Survey of Korean Medicine Doctors

Article information

Abstract

Background

The applicability of Korean medicine (KM) treatments for post-acute COVID-19 syndrome were investigated.

Methods

A cross-sectional, web-based survey of Korean medical doctors (KMDs) was conducted in June 2022. The 25-item questionnaire comprised of five parts: basic characteristics, prescribed post-COVID-19 KM treatments, treatment effect in patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, patient satisfaction, and awareness and utilization of the relevant KM Clinical Practice Guideline by the KMDs.

Results

In total, 1,063 completed questionnaires were collected, and 822 were analyzed. The most common symptoms in patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome treated by KMDs was weakness and fatigue (84.3%). Herbal decoctions (39.2%) and herbal powder (not covered by medical insurance; 25.8%) were primarily used. Among the KMDs, 95% (n = 781) responded that KM treatments, particularly herbal decoctions (82.6%) and herbal powder (not covered by medical insurance; 46.8%), were effective. Overall, 92.6% (n = 761) of KMD participants answered that the patients were satisfied with KM treatments, mostly due to symptomatic improvement (60.8%). The primary reason for dissatisfaction was the burden of cost for patients (78.4%). The main reasons for low uptake of KM services by patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome were lack of publicity and administrative issues such as no health insurance coverage.

Conclusion

KM is highly applicable for post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Health policies supporting the use of KM for post-acute COVID-19 syndrome are recommended.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has spread rapidly since it was first reported in 2019 [1]. SARS-CoV-2 affects multiple organs, causing a wide range of symptoms including respiratory and pulmonary symptoms such as fever, coughing, sputum, and fatigue, diarrhea, heartburn, and headache [1,3]. The severity of COVID-19 symptoms ranges from asymptomatic infection to the patient being in a critical state, and age and comorbidities are significant risk factors for severe COVID-19 [4–6].

In many noncritical cases, COVID-19 symptoms resolve within 2–4 weeks. However, some patients experience symptoms that persist, and some symptoms are new developments, or worsen after 1 month [7,8]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, has defined symptoms that are present for 4 weeks or longer after infection with SARS-CoV-2 as post-COVID condition or long COVID [9]. In the following of this paper, we will use the commonly used ‘long COVID’ instead of the MESH term ‘post-acute COVID-19 syndrome’.

The exact number of cases affected by long COVID differ across studies; long COVID have been reported in as little as 30% and as high as 80% among COVID-19 patients [10–12]. Long COVID comprise a wide range of symptoms. Weakness and fatigue are typical symptoms of post-COVID. In addition, patients with long COVID presented with symptoms including musculoskeletal pain, coughing, chest pain, dyspnea, anosmia/dysgeusia, headache, diarrhea, anxiety and depression, and sleep difficulties [10–12]. In one study, conducted on patients 6–12 months after COVID-19, more than half of the study participants experienced long COVID with symptoms such as fatigue, impaired memory, anxiety, and depression [13–15].

Recent studies have shown clinical evidence for the effectiveness of traditional medicine (TM) or complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) such as Chinese medicine, Kampo medicine, and Korean medicine (KM) for the treatment of COVID-19 [16–19]. Patients with mild illness who received Chinese herbal medicine showed a high recovery rate and short time-to-recovery [20], and those with severe COVID-19 showed a lower mortality rate [21]. In particular, Chinese medicine has been reported to play an important role in the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome; the use of Chinese medicine is common in Chinese communities, with 90% of COVID-19 patients reportedly using Chinese medicine [22,23]. However, no standard TM/CAM treatment has been established for long COVID, and there have been a limited number of related studies compared with studies on the treatment of acute COVID-19 symptoms.

Considering the importance of holistic and multidisciplinary approaches in the management of patients with long COVID [24,25], TM/CAM may be an effective treatment. In South Korea, the Association of Korean Medicine (AKOM) operated the “COVID-19 Telemedicine Center of Korean Medicine (KM telemedicine center), and many patients in the subacute or chronic stage of COVID-19 reported significant improvement in all symptoms, including headache, cough, and sore throat, after completing the KM treatment program directed by this center [26]. However, only a few related studies have been reported.

In this study, a survey was conducted on KM doctors (KMDs) in a clinical setting who have experienced the treatment of patients with COVID-19 or long COVID. Using a questionnaire on treatment experiences including type of therapies employed, treatment duration, and treatment effects, the applicability of KM for the treatment of patients with long COVID was examined.

Materials and Methods

1. Study design

A cross-sectional study based on a web-based survey of KMDs who were registered with the AKOM was conducted in South Korea in June 2022. The AKOM allows collective text messages and e-mails to be sent to registered KMDs to complete surveys for academic and public-interest purposes. The e-mails related to the survey conducted in this study were sent twice: on May 25, 2022, and on June 8, 2022. Survey data were collected in May and June 2022.

Prior to the initiation of the survey, all participants provided informed consent via an online consent process which replaced written consent. The consent form included a brief introduction to the purpose of the study, the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the privacy and confidentiality policy. Only KMDs who provided consent on the form participated in the online questionnaire. Anonymity was guaranteed for all respondents, and the data which the researchers gained access to were encrypted to ensure anonymization of personal identifiable information. Confidentiality was maintained by restricting the permission of access. Only the principal investigator, investigators, and the statistician of this study had access to the raw data.

Raw data were cross-checked by the statistics data manager prior to analysis. The reliability of the survey was ensured by removing surveys that were incomplete or had critical or logical errors in the responses. Respondents who replied in duplicate were identified based on their telephone numbers and removed. The telephone number was only used for the identification of duplicate responses and was immediately deleted.

This study complied with the checklist for reporting of survey studies, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine (approval no.: JASENG 2022-05-006; approval date: 20 May 2022).

2. Participants

Eligible participants of the survey were KMDs who were members of the AKOM and had experience in treating COVID-19 and long COVID in a clinical setting. The inclusion criteria were KMDs with treatment experience in COVID-19 or long COVID, and those who consented to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were KMDs who were not registered with the AKOM, did not work in a medical institution, or did not consent to study participation.

3. Survey

This questionnaire was developed through a literature review of prior studies and by discussions with researchers. The questionnaire consisted of 25 questions, in five parts. The expected time required to complete the survey was approximately 10 minutes. Details of the questionnaire were presented separately (Supplementary 1).

4. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were analyzed for respondents’ basic characteristics and content of the questionnaire. The mean ± SD was used to express continuous variables, and frequency (%) was used for categorical variables. Since the survey items on herbal powders and herbal decoction prescriptions were open-ended, the collected responses were highly heterogeneous and included modified prescriptions. Thus, two KMDs with more than three years of clinical experience categorized the respective prescriptions, carried out cross-checks, and held discussions to produce a unified prescription category. Frequency analysis was performed according to the determined categories. Missing data were analyzed without imputation. All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R-4.2.1 for Windows (The R Foundation).

Results

1. Basic characteristics of the KMD respondents

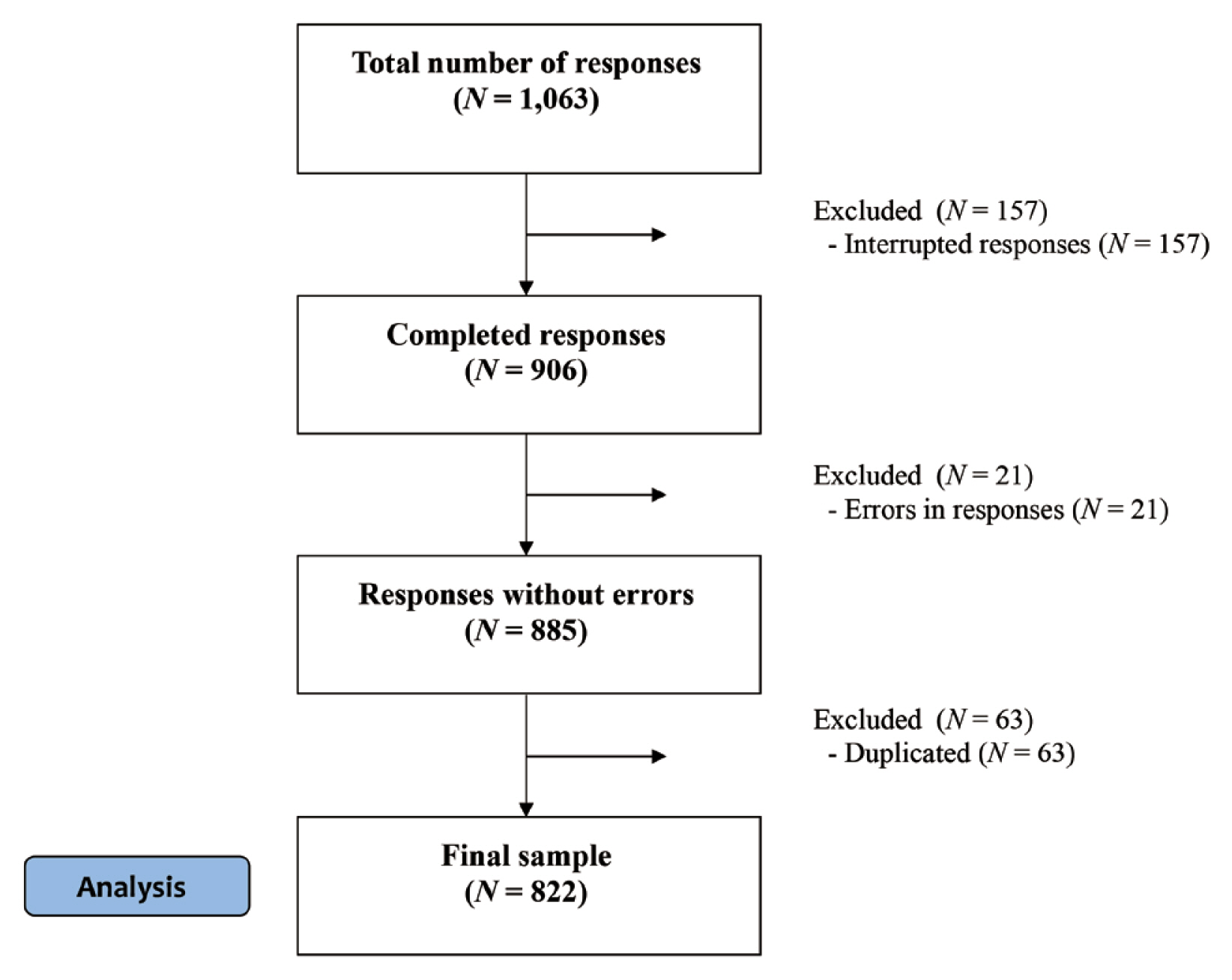

In total, 1,063 completed questionnaires were collected. Of these, 157 incomplete responses and 21 responses with logical errors were excluded to prevent possible compromise in data reliability. In the case of duplicated responses, the survey values with a higher completion rate were used as the default; if both surveys were fully completed, the earlier response was used. A total of 63 questionnaires were excluded because of duplicate responses. There were 822 responses analyzed (Fig. 1).

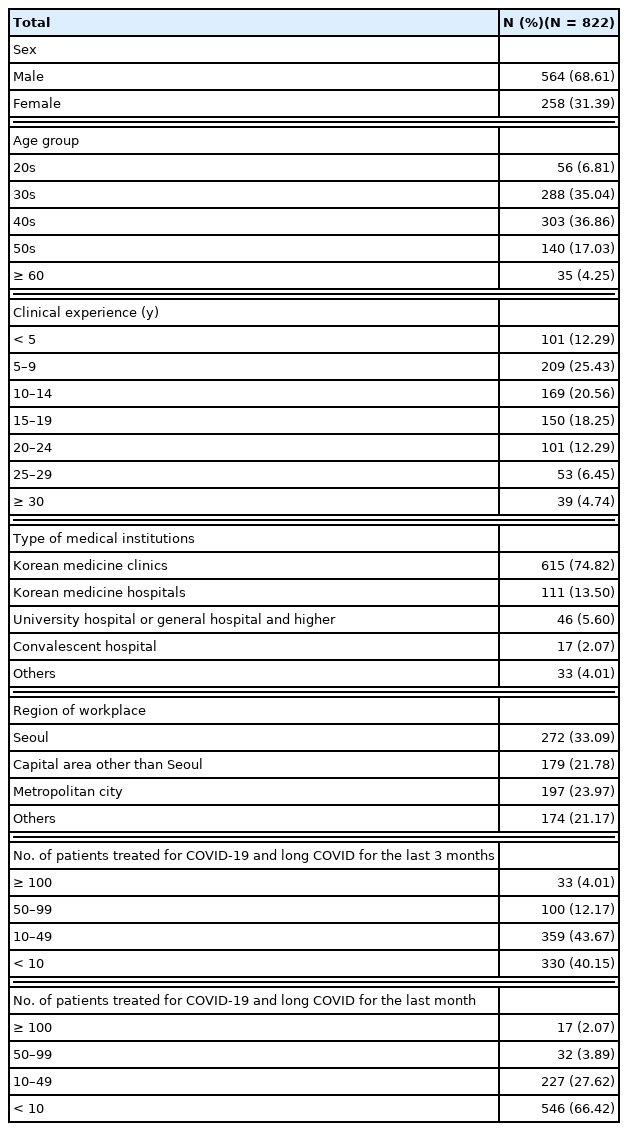

The respondents’ basic characteristics are listed in Table 1. In brief, of the 822 respondents in total, 564 (68.6%) were male. By age groups, KMDs in their 40s (303; 36.9%) and 30s (288; 35.0%) accounted for the highest proportion of respondents. For clinical experience, those KMDs with more than 5 years and less than 10 years accounted for the most respondents with 209 KMDs (25.4%), in this category followed by those with more than 10 years and less than 15 years where there was 169 KMDs (20.6%), and those with more than 15 years and less than 20 years with 150 KMDs (18.25%). Thus, most KMDs were distributed in the range of 5 years ≤ clinical experience ≤ 20 years. In terms of the number of patients treated for COVID-19 and long COVID in the last 3 months, those KMDs who treated < 10 patients and those who treated 10–49 patients accounted for the highest proportions, 330 (40.15%) and 359 KMDs (43.67%), respectively, while only 33 KMDs (4.0%) treated more than 100 patients. The most frequent number of patients treated for COVID-19 and long COVID for the last month was fewer than 10 patients where 546 (66.4%) patients were treated.

2. Treatment of long COVID

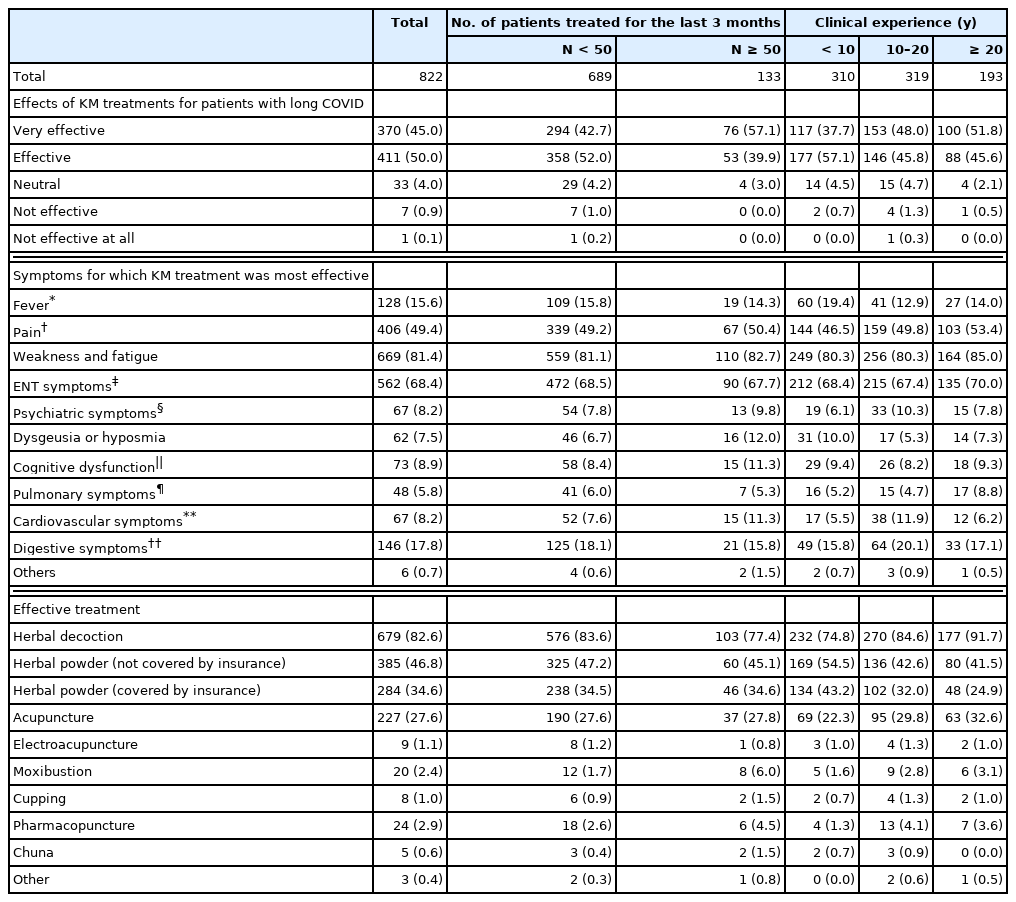

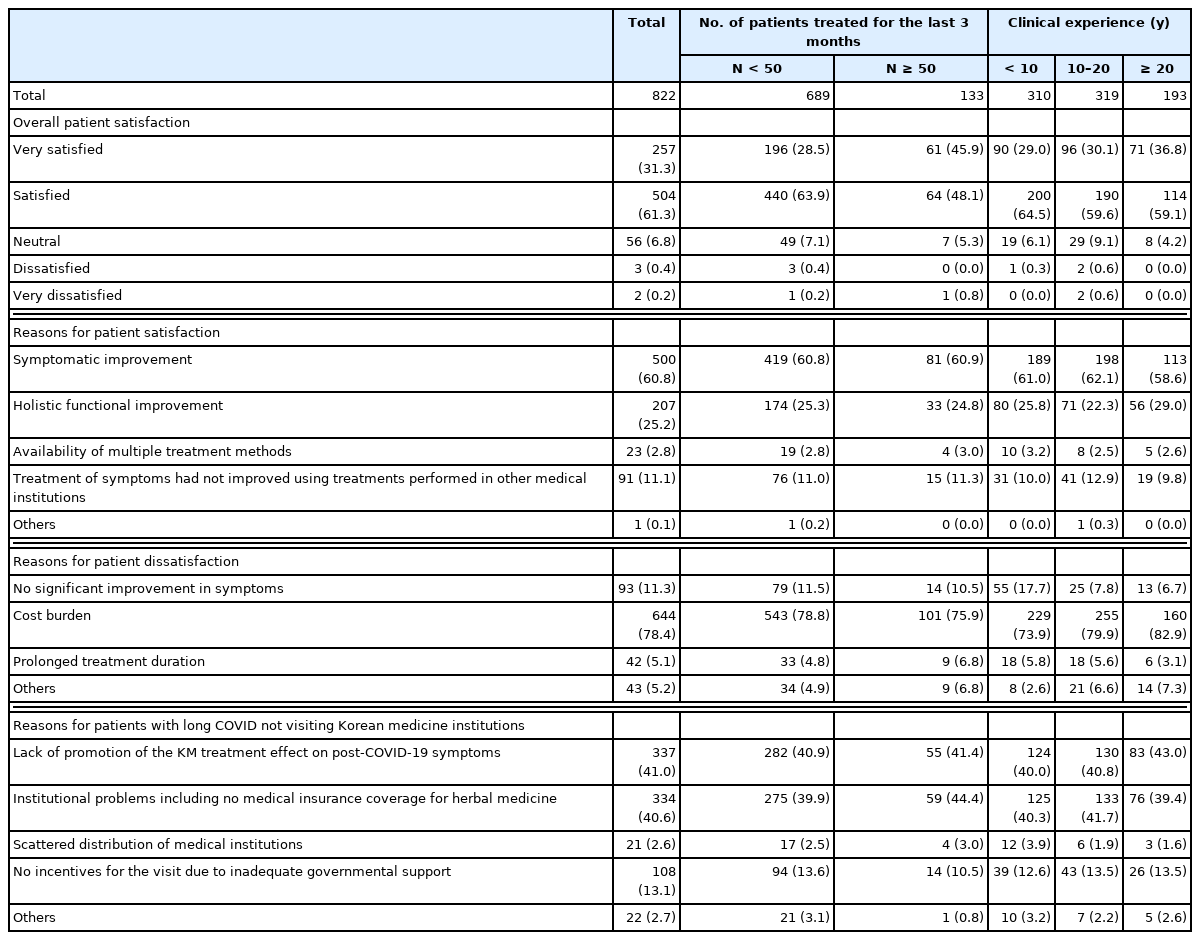

The number of patients, their symptoms and treatment, and the years of clinical experience of the KMDs are shown in Table 2. The two predominant chief complaints made by the patients were weakness and fatigue (n = 693; 84.3%) and ear, nose, and throat (ENT) symptoms (n = 627; 76.3%). The most-used treatments were herbal decoction (n = 322; 39.2%), followed by herbal powders (not covered by medical insurance; n = 212; 25.8%). Analyzing by clinical experience, the clinical experience of the KMDs and the use of herbal decoction positively correlated. The second most-used treatment was acupuncture (n = 251; 30.5%) and herbal powder (covered by medical insurance; n = 232, 28.2%; Fig. 2).

KM treatments for patients with post-COVID-19 symptoms. (A) the most used; (B) the most effective treatment. Each treatment method is represented in terms of % against the most-used treatment, the second most-used treatment, and the most effective treatment.

HD, herbal decoction; HP (not cv), herbal powder (not covered by medical insurance); HP (cv), herbal powder (covered by medical insurance); Acu, acupuncture; E. Acu, electroacupuncture; Moxi, moxibustion; Ph. acu, pharmacopuncture; KM, Korean medicine.

In the case of herbal decoction prescription, the mean duration, of a single prescription, of medicine was for 14.1 ± 8.4 days, and the duration was shorter in the KMD group with less than 10 years of clinical experience (12.1 ± 7.2 days). Overall, 124 KMDs (25.0%) answered that they prescribed Bojungikgi-tang, making this the most frequently prescribed herbal decoction. In the case of herbal powder (not covered by medical insurance) prescriptions, the mean duration, of a single prescription, of medicine was 10.47 ± 8.50 days, and the most frequently prescribed herbal powder was also Bojungikgi-tang (n = 85; 15.4%). The prescription pattern of herbal powders and herbal decoction prescriptions were similar to one another.

The average number of treatments was 3.16 ± 3.01, which was higher in the group with ≥ 50 patients treated (4.38 ± 5.57) than in the group with < 50 treated patients (2.92 ± 2.12). The expected treatment duration explained to the patient was 3.72 ± 5.14 weeks. Clinicians with more than 20 years of clinical experience had a tendency of describing the course of treatment as longer (4.84 ± 7.23 weeks).

3. Effects of KM treatments in patients with long COVID

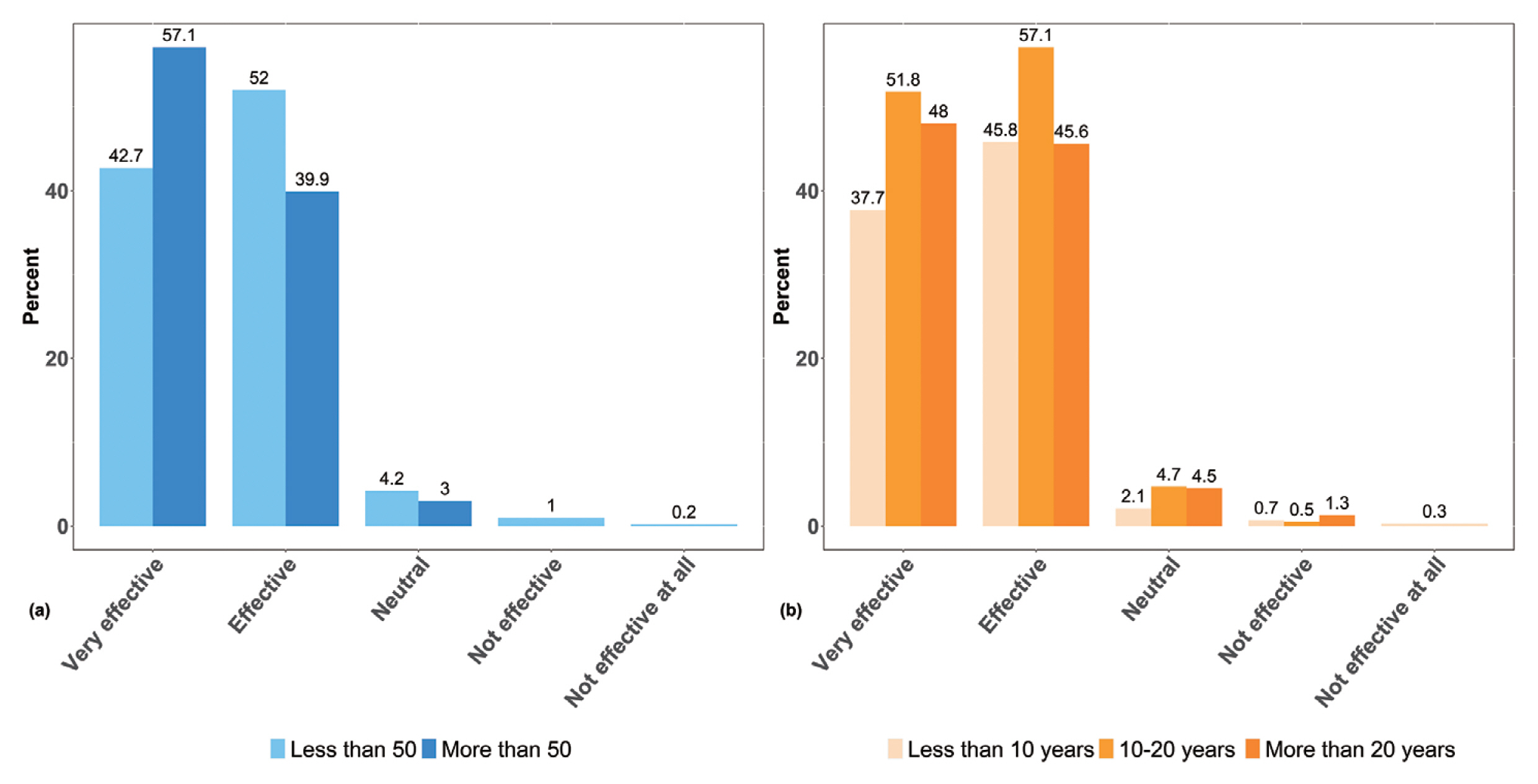

In this investigation of the treatment effects of KM on long COVID, 95% of respondents (n = 781) answered that KM treatments were very effective or effective. Only 1.9% (n = 8) of the KMDs answered that the KM treatment used was ineffective (Table 3, Fig. 3). In particular, in the group with a large number of treated patients and in the group of KMD with more than 10 years clinical experience, the higher the proportion of respondents who answered that KM treatments were very effective. The symptoms for which KM treatment was the most effective were weakness and fatigue (n = 669; 81.4%), ENT symptoms (n = 562; 68.4%), and pain (n = 406; 49.4%). The most effective treatment was herbal decoction (n = 679; 82.6%), followed by herbal powder (not covered by medical insurance; n = 385; 46.8%), and herbal powder (covered by medical insurance; n = 284; 34.6%). Therefore, a large number of the KMD respondents answered that herbal medicine was an effective treatment (Fig. 2).

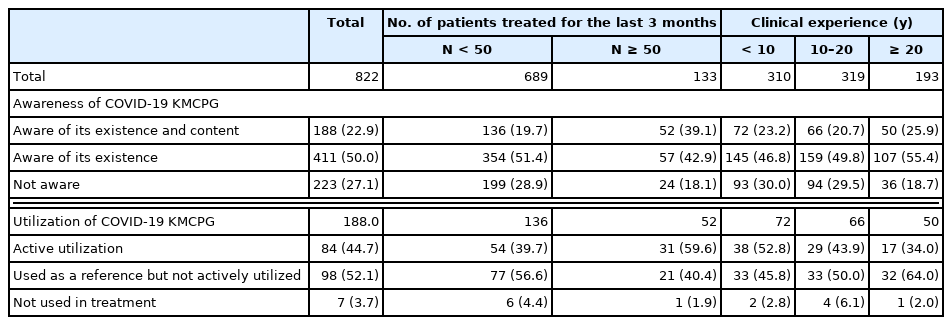

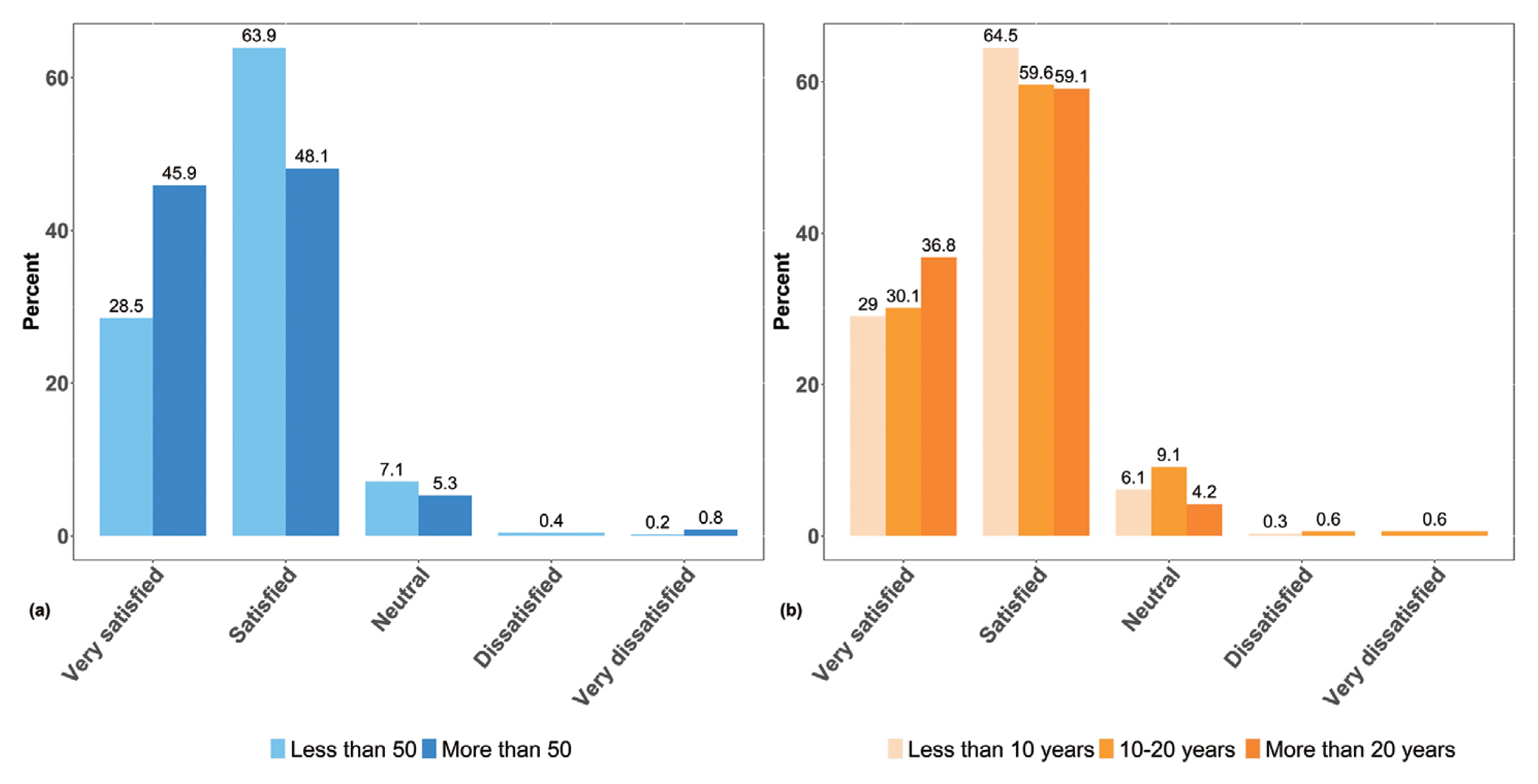

4. Satisfaction with KM treatment in patients with long COVID

Patient satisfaction with KM treatment is illustrated in Table 4 and Fig. 4. In response to patient satisfaction with KM treatments, 257 KMDs (31.3%) answered that patients were very satisfied and 504 KMDs (61.3%) answered that patients were satisfied, indicating that 92.6% of the respondents answered that patients were satisfied with KM treatments. Five KMDs (0.6%) answered that patients were either dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. The percentage of KMDs who responded that patients were very satisfied was higher in the group with a larger number of treated patients, and the group with longer clinical experience responded with a higher ratio of patient satisfaction.

Patient satisfaction with KM treatment of post-COVID-19 symptoms: (A) according to the number of patients; and (B) clinical experience.

KM, Korean medicine.

In terms of the reasons for patient satisfaction, 500 KMDs (60.8%) selected the effect of KM upon symptomatic improvement, 207 KMDs (25.2%) selected holistic functional improvement, and 91 KMDs (11.1%) selected treatment with KM for symptoms that had not improved using treatments performed at other medical institutions. As for the reasons for patient dissatisfaction, the burden of cost was most commonly cited (644 KMDs, 78.4%). In terms of the main reasons for patients with long COVID not visiting KM institutions, 337 KMDs (41.0%) reported a lack of promotions advertising the effects of KM treatments, and 334 people (40.6%) selected inadequate governmental support.

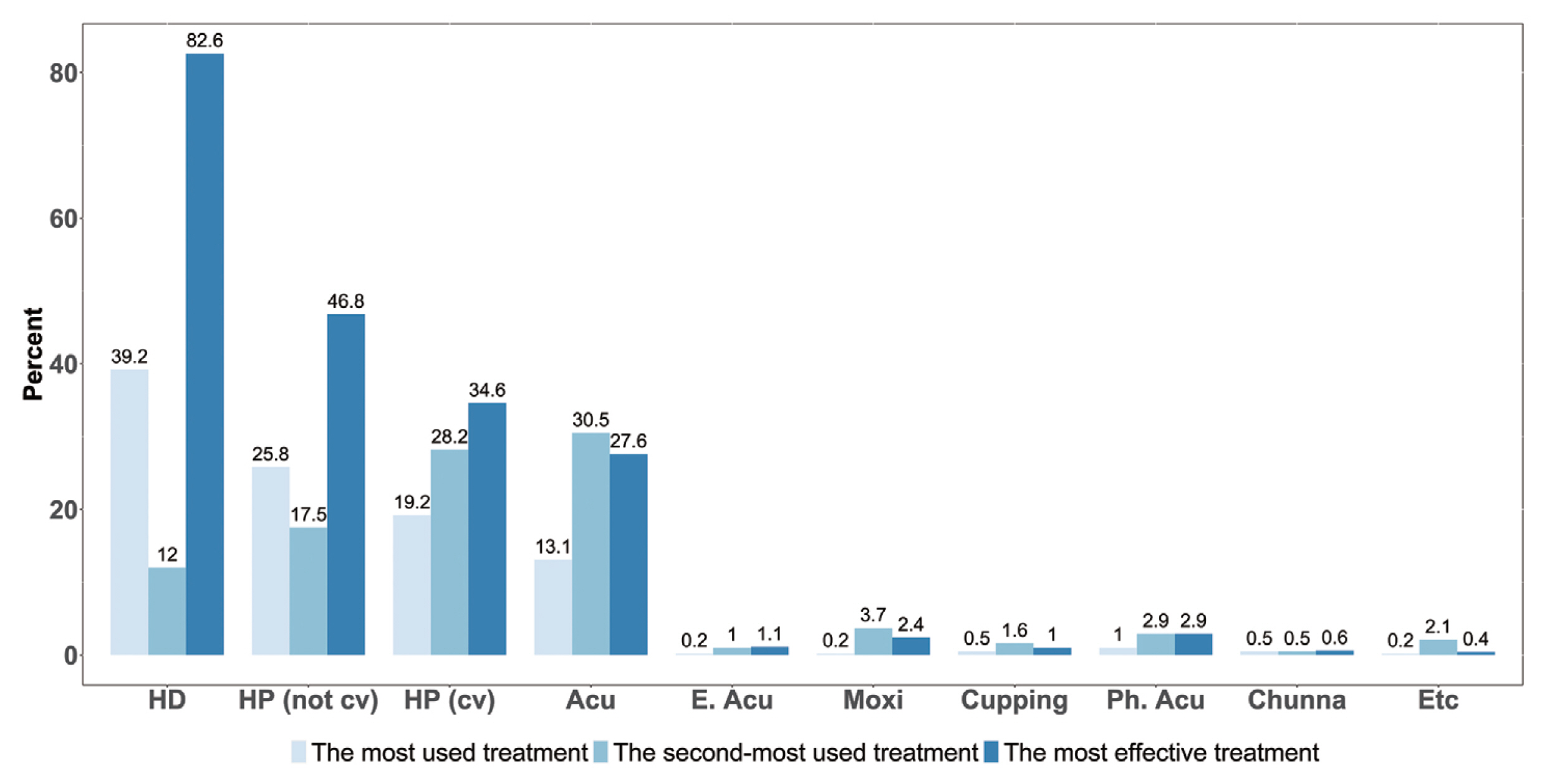

5. Korean Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline

Regarding the awareness of the existence of the COVID-19 Korean Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline (KMCPG) published in March 2020, 188 respondents (22.9%) answered that they were well aware of the KMCPG and its contents (Table 5). The percentage of respondents who were aware of the contents of the COVID-19 KMCPG was higher in the group with a large number of treated patients. Of the 188 KMDs who answered that they were aware of the contents of the KMCPG, 84 (44.4%) answered that they were actively using the treatment guideline. The rate of active use of the KMCPG was higher in the group with a large number of treated patients, and in the group with less than 10 years of clinical experience.

Discussion

Several waves of COVID-19 outbreaks and subsequent mutations of the coronavirus have caused both acute and chronic symptoms in patients, many of which are still being investigated. In South Korea, patients with long COVID sometimes visit KM clinics and hospitals for KM treatment under the dual medical system in which KM and Western medicine clinics are separate independent medical clinics. No studies to date have been conducted on KM treatments for long COVID. This web-based survey, completed by KMDs, is the first study investigating KMDs experience in treating patients with COVID-19 and long COVID, the treatment methods used, the effects of KM treatment, and patient satisfaction.

The typical chief complaints of the patients were weakness and fatigue (n = 693; 84.3%), and ENT symptoms (n = 627; 76.3%); the most commonly used treatments were herbal decoction (n = 322; 39.2%) and herbal powder (not covered by medical insurance; n = 212; 25.8%). Bojungikgi-tang was the most frequently prescribed herbal medicine for both herbal decoction and herbal powder (not covered by medical insurance). The average duration, of a single prescription, for the herbal decoction and herbal powder was 10–14 days, and the average number of treatments used was 3.16 ± 3.01.

The most commonly cited symptom among the patients’ chief complaints were weakness and fatigue, which were reported as the most common long COVID symptoms in a number of previous studies [10–13]. However, ENT symptoms reported in this study, which accounted for the second highest percentage of chief complaints, differed from what was reported in previous studies which mentioned shortness of breath, dysgeusia or hyposmia, joint pain, muscle pain, and sleep difficulties [8,10,11,27–32]. This difference may be due to the characteristics of patients visiting KM clinics and hospitals; or it may also be a characteristic of the late-stage epidemic factors. Although it is not possible to determine the exact reason from this study, it seems that the latter is more likely, since ENT symptoms are not the foremost reasons to visit KM clinics, and it is more likely that musculoskeletal symptoms are usually the main concern [33].

For the most used treatment, the commonly selected responses by the KMDs were herbal decoction, herbal powder (not covered by medical insurance), and herbal powder (covered by medical insurance), in that order, indicating that herbal medicine treatment was frequently used for patients with long COVID. The most frequently prescribed herbal medicine was Bojungikgi-tang, which is known as Hochuekki-To in Japan and Buzhongyiqi-tang in China. In a meta-analysis based on analyses of seven randomized controlled trials, Bojungikgi-tang significantly improved the overall symptoms of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome [34]. Sipjeondaebo-tang, another frequently prescribed herbal medicine, is a representative restorative herbal medicine that is used for fatigue, loss of energy, loss of appetite, and energy loss after illness [35]. Ssanghwa-tang is also used to treat health conditions involving qi and blood deficiency [36]. Given that weakness and fatigue are the most cited symptoms of long COVID, it can be inferred that a prescription for herbal medicine to improve weakness were the top choice for most KMDs.

Most of the respondents (n = 781; 95.0%) answered that KM treatments showed effectiveness when they treated the patients with post-COVID-19 symptoms. The symptoms for which KM treatments were the most effective were weakness and fatigue (n = 669; 81.4%) and ENT symptoms (n = 562 patients; 68.4%). The most effective treatments were herbal decoction (n = 679; 82.6%) and herbal powder (not covered by medical insurance; n = 385; 46.8%). In addition, 92.6% (n = 761) of the KMDs who answered that patients were satisfied with KM treatment, and the most common reason for satisfaction was symptomatic improvement (n = 500; 60.8%).

Williams et al [37] argued that long COVID could be improved based on the principles of acupuncture such as vagal tone regulation, chronic inflammation management, reactive oxygen species modulation, and that a holistic and multi-disciplinary approach is required for adequate care and management of patients with long COVID [24,25]. Considering the findings of these studies, traditional medicine may be used as an effective treatment for symptoms of long COVID, and the results of this survey further support the applicability of KM treatment.

Despite the high level of satisfaction of patients with long COVID visiting KMDs, patients with long COVID do not usually visit KM clinics. In fact, 66% of the KMDs answered that they treated fewer than 10 patients in the last month. The main reasons for patients not visiting KM institutions were identified in this survey as a lack of publicity that KM treatment is effective in the treatment of long COVID. Furthermore, administrative issues including a lack of medical insurance coverage for herbal medicine has probably limited the uptake in KM healthcare. In particular, herbal medicine is widely used and considered to be effective for long COVID treatment, but national health insurance only covers a small number of herbal powders, which may also act as an obstacle to the use of KM services. This result is supported by the fact that burden of cost was by far the most cited reason for patient dissatisfaction (644 patients; 78.4%). Therefore, there is a pressing need for financial support from national health insurance to cover more herbal medicines for patients with long COVID to guarantee the treatment rights of these patients.

Since this study was designed as web-based survey research conducted using a questionnaire sent through e-mail, KMDs who do not check their e-mail often may have been excluded from participating in the survey. Nevertheless, by sending a questionnaire to all AKOM-registered KMDs, this study aimed to ensure a representative sample of South Korean KMDs. Considering the age and regional distribution of the respondents, the sample of this survey was considered representative. In addition, patient satisfaction and reasons for satisfaction were indirectly examined by KMDs rather than directly by the patients. However, it was judged that the responses obtained in this study were credible because the effects of KM treatments and patient satisfaction were highly rated in the group of KMDs who treated a large number of patients, and in the group of KMDs with many years of clinical experience.

In conclusion, this study investigated the current status and effects of KM treatments for long COVID, which have not been reported previously. The effectiveness of KM on long COVID treatment and the positive response in terms of patient satisfaction were confirmed, indicating the applicability of KM treatments for long COVID. In addition, limitations such as lack of health insurance coverage for herbal medicine increased the cost burden for patients, which was shown to be an obstacle to using KM treatments. The results of this study provide a reference for KMDs treating patients with long COVID as well as for policymakers in the future.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material is available at doi: https://doi.org/10.56986/pim.2022.09.006.

Notes

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: DK. Methodology: DK, SHP. Formal investigation: EJK. Data analysis: DK. Writing original draft: DK. Writing - review and editing: WSS, and EJK.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

None.

Ethical Statement

The present study referred to the Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies, and the study protocol and questionnaire were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine (approval no.: JASENG 2022-05-006; approval date: 20 May 2022).

Data Availability

Raw data cannot be disclosed, and all relevant analyzed data were included in the manuscript and supplementary section.