Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Perspect Integr Med > Volume 2(2); 2023 > Article

-

Review Article

A Scoping Review of Clinical Research on Motion Style Acupuncture Treatment -

Doori Kim1

, Yoon Jae Lee2

, Yoon Jae Lee2 , In-Hyuk Ha2,*

, In-Hyuk Ha2,*

-

Perspectives on Integrative Medicine 2023;2(2):65-76.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.56986/pim.2023.06.001

Published online: June 23, 2023

1Department of Korean Rehabilitation Medicine, Bucheon Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine, Buchoen, Republic of Korea

2Jaseng Spine and Joint Research Institute, Jaseng Medical Foundation, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- *Corresponding author: In-Hyuk Ha, Jaseng Spine and Joint Research Institute, Jaseng Medical Foundation, 540, Gangnam-gu, Seoul, 06110 Republic of Korea, Email: hanihata@gmail.com

©2023 Jaseng Medical Foundation

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

- 2,306 Views

- 45 Download

- 3 Crossref

Abstract

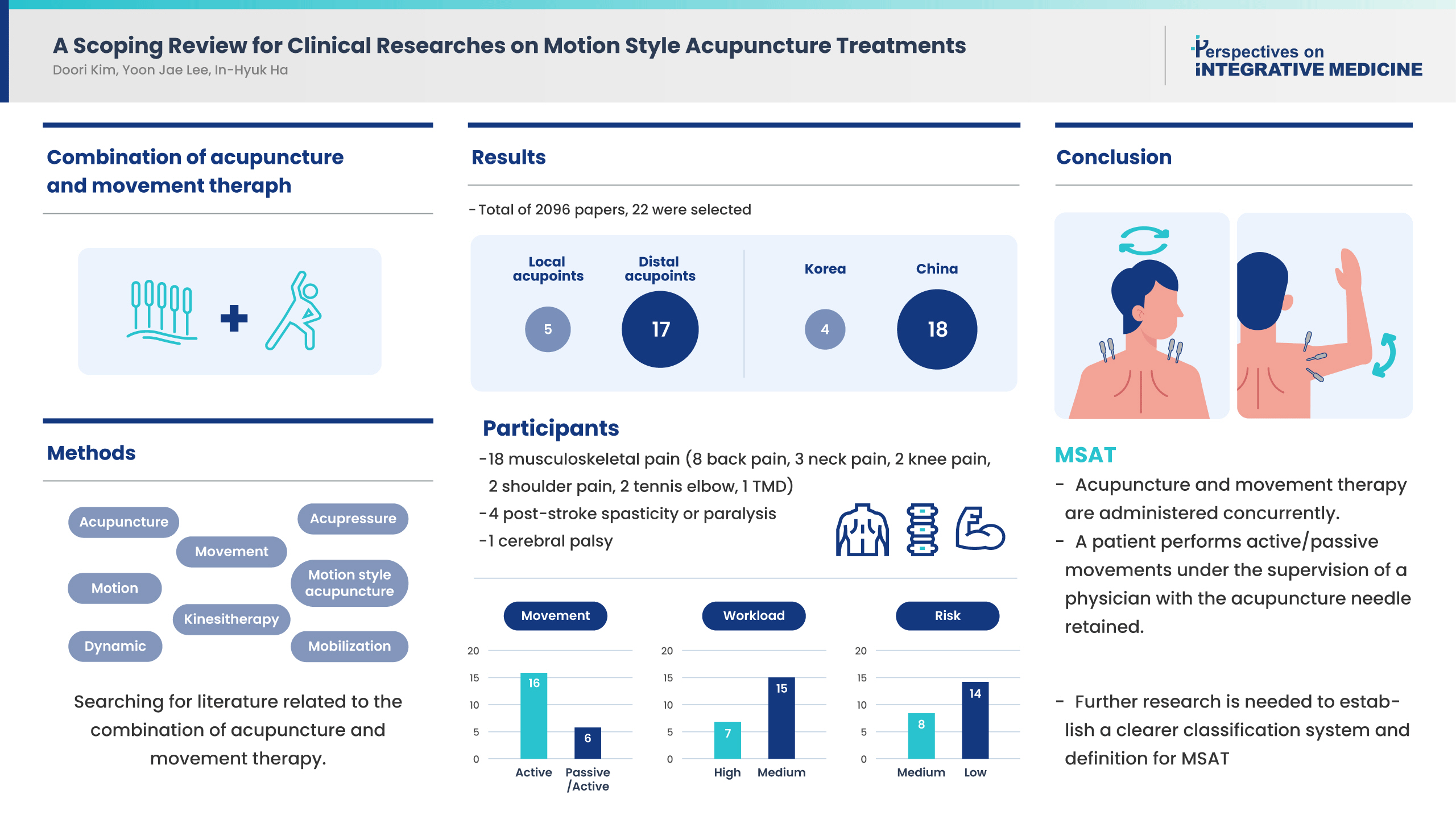

- This scoping review was conducted to examine the concept of Motion style acupuncture treatment (MSAT), use in clinical practice, its effectiveness, and safety. A literature review of clinical study treatment methods combining acupuncture and movement therapy was performed using PubMed. Of 2,096 studies retrieved, 22 were included in this review. There were 12 randomized controlled trials, and all 22 studies were published in China and Korea, mostly, within the last 3 years. There were five studies concerning local acupoints and 17 studies regarding needling at distal acupoints, and the level of risk of the procedure was “high” in eight studies and “moderate” in 14 studies. The study participants were patients with musculoskeletal pain, and many studies reported significant improvements in pain and functional disability outcomes following treatment using MSAT. For conclusion, MSAT refers to a treatment method in which a patient performs active/passive movements under the supervision of a physician with the acupuncture needle retained at the insertion site. However, there are a limited number of MSAT studies, and various treatment types and related terms are mixed. Further studies, classification of the types of MSAT using a well-established classification system, and a clearer definition of the MSAT concept are needed.

- Acupuncture is an important treatment modality that has been used for thousands of years in East Asian countries, including China, Japan, and Korea [1]. Acupuncture is based on the theories of “meridians” and “qi” (the principles of traditional medicine in East Asia) [2]. Although there is no clear definition of qi, it is a type of energy that connects all phenomena and objects, and explains changes; qi is believed to circulate around the human body. Meridians are special channels for the flow of qi, and acupuncture is performed, mainly, by stimulating 365 acupoints on the body that are specific to the meridians [1,3].

- Acupuncture was introduced to the West in the early 1970s and has since grown in popularity [1]. Thus, active research has been performed on acupuncture, and theories for the interpretation of its mechanisms have been presented from a modern perspective. Of the representative explanations on the mechanisms of acupuncture, the “gate control theory” [2,4,5] proposes that different afferent fibers are activated by acupuncture, which in turn restricts the pain signals from travelling to the brain. Another theory on the possible mechanism is that acupuncture stimulates pain receptors to release endogenous opioids and other neurotransmitters [2,6].

- Apart from the traditional methods of acupuncture where dry needles are inserted into points along the meridian and acupoints, acupuncture has continued to evolve and develop. In China, Japan, and Korea, various methods such as ear, scalp, and hand acupuncture have been developed over thousands of years [7]. In the West, studies have investigated the correlation between acupuncture and trigger points [8]. Particularly, in modern times, a range of approaches have been introduced and applied to increase stimulation and maximize the effect of acupuncture.

- Electroacupuncture is a representative stimulation method which uses two dry needles as electrodes. The needles are inserted into the skin and an electric current is transmitted through the needles into the human body, thereby enhancing the level of stimulation delivered from acupuncture [9]. Electroacupuncture produces a more widespread signal increase on functional magnetic resonance imaging than by manual acupuncture [9]. In addition, one study confirmed that electroacupuncture had greater effects on cell proliferation and neuroblast differentiation than manual acupuncture, increasing the number of dendrites in the rat hippocampus [10]. In several clinical studies that have compared the effectiveness of electroacupuncture and acupuncture, greater effects of electroacupuncture over acupuncture have been reported in the treatment of different conditions including tennis elbow [11–15].

- In many cases, acupuncturists enhance acupuncture stimulation by inducing the de qi sensation through different acupuncture manipulations [16,17]. After the needle penetrates the skin and is inserted to the desired depth, acupuncturists apply stimulation, such as lifting, thrusting, twirling, and rotation, by manipulating the needle [18]. Such different methods of acupuncture manipulation were associated with an increase in the skin temperature [19] and greater cerebral activation on functional magnetic resonance imaging [20]; moreover, the acupuncture manipulation showed greater analgesic effects than acupuncture without or with little manipulation [21,22].

- The effect of acupuncture can also be enhanced by applying stimulation through movement after needle insertion. Shin et al [23] introduced motion style treatment and reported the effects in two patients presenting with severe acute low back pain (LBP) whose pain improved with motion style treatment. Later, this method became more commonly referred to as motion style acupuncture treatment (MSAT). MSAT is widely used to reduce musculoskeletal pain in the clinical practice of Korean medicine [24–27], and its use is increasing not only in Korea, but also in China [28,29]. However, very few studies have been published on MSAT, and general matters such as the concept of MSAT that can be used based on consensus, have not yet been established.

- Herein, we conducted a literature review on the combined treatment of acupuncture and movement therapy to examine the concept of MSAT, status of use in clinical practice, effectiveness, and safety.

Introduction

- 1. Data sources and search strategy

- We searched for literature related to the combination of acupuncture and movement therapy using the PubMed database from the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE). The search strategy was as follows: [(“acupuncture[Title/Abstract]” or “needling[Title/Abstract]” or “acupressure[Title/Abstract]”) and (“movement” or “motion” or “dynamic” or “mobilization” or “kinesitherapy”)] or “motion style acupuncture.”

- 2. Study selection

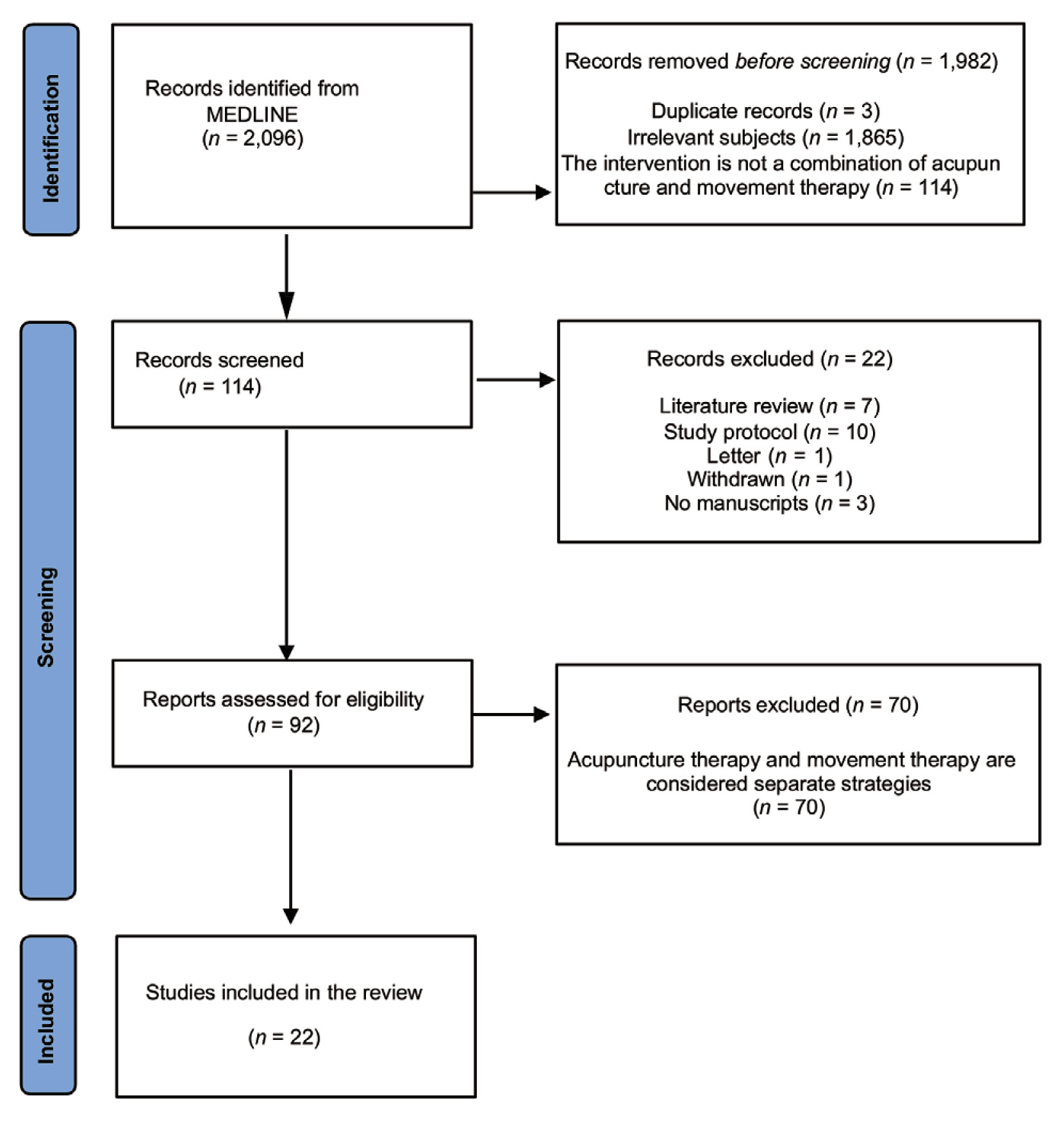

- All clinical studies, including case reports or case series, in which the intervention was a combination of acupuncture and movement therapy, were included. In vivo and in vitro studies that did not involve human participants were excluded from the screening process. Additionally, reports such as literature reviews, study protocols, or letters, and those studies in which acupuncture therapy and movement therapy were considered separate strategies were excluded, as were cases where the original manuscripts could not be found.

- 3. Data extraction

- For all the studies identified through the search, those with irrelevant research topics were excluded before screening by checking only the titles and abstracts. Two researchers performed the process independently, and different opinions on studies were reviewed to determine the inclusion/exclusion status.

- For the studies selected in the first stage, eligibility was assessed to determine the final status of inclusion/exclusion. The following data were extracted: author(s), year of publication, country of origin, study design, participants (disease and sample number), type of intervention, comparators, acupuncture points used for the intervention, types of movement therapy, number of treatment sessions, outcomes, workload of physician, risk of the therapy, main results related to the treatment effects, and adverse events.

- Workload of the physician and risk of the therapy were classified into high, moderate, and low, separately. For workload, when the physician held the patient’s body and directly made passive movements for treatment, it was classified as “high,” and when assisting and guiding the patient’s active movements, it was classified as “moderate.” The risk was determined by the research team, considering the area of acupuncture and movement. In particular, risk was classified as “moderate” if the treatment was by moving the acupuncture treatment area.

Materials and Methods

- 1. General characteristics of the included studies

- From a total of 2,096 studies retrieved from the PubMed database (MEDLINE), 22 were selected and reviewed according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Interventions that combined acupuncture and movement therapy were classified into Types. Type 1 treatment in which a needle was inserted in the affected region (local acupoints), and active/passive movement was applied at the point of needle insertion. Type 2 acupuncture was performed at distal acupoints, followed by active/passive movement without needle retention. In all the selected studies, acupuncture and movement therapy were performed simultaneously. In other words, movement therapy was performed while the acupuncture needle was inserted into the body. A summary of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

- Of the 22 selected studies, there were five Type 1 and 17 Type 2 treatments. For Type 1, three studies originated in China and two in Korea; for Type 2, 15 studies originated in China and two in Korea. No studies retrieved were published outside of Korea and China.

- Among the 22 selected studies, eight were published within the last 3 years (2020–2022); no studies were published before 2010. This finding demonstrated that the combination of acupuncture and movement therapy is a relatively new treatment method.

- Different names were used for the treatment method depending on the study, but MSAT (Type 1, two studies; Type 2, four studies) was most commonly used, followed by exercise acupuncture (Type 1, one study; Type 2, three studies). The following names were reported in one study each: dynamic qi acupuncture (Type 2), balanced acupuncture (Type 2), and acupuncture-movement therapy (Type 2). In other studies, the name of the treatment method was only expressed as acupuncture combined with movement therapy.

- Of the 22 selected studies, there were 12 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Type 1, two; Type 2, ten), three prospective comparative observational studies (Type 1, one; Type 2, two), five case series (Type 1, two; Type 2, three), and two retrospective reviews of medical records (Type 2).

- 2. Participants

- Most patients in the selected studies had musculoskeletal pain. There were eight studies (Type 1, one; Type 2, seven) on patients with LBP and radiating leg pain, which accounted for the highest proportion of the included studies, followed by three cases of neck pain (Type 1, one; Type 2, two), 2 cases of knee pain (Type 2), two cases of shoulder pain (Type 2), two cases of tennis elbow (type 2), and one case of temporomandibular disorder (TMD) (Type 1), indicating that 18 studies were conducted in patients with musculoskeletal pain. Additionally, there were four studies (Type 1, two; Type 2, two) in patients with post-stroke spasticity or paralysis, and 1 study (Type 2) in a pediatric patient with cerebral palsy.

- 3. Type of intervention

- Details of the interventions for the individual studies are outlined in Table 2. In 13 studies (Type 1, four; Type 2, nine), a combination of acupuncture and movement therapy was performed as an add-on to conventional Korean medicine treatment and other treatments, and for the remaining nine studies, the combination of acupuncture and movement therapy was the only intervention applied. Among the intervention methods performed with a combination of acupuncture and movement therapy, conventional rehabilitation accounted for the highest number of cases, followed by integrative Korean medicine (IKM) treatment in 3 cases, and acupuncture in three cases. In two studies, special manipulation and infrared therapies were performed along with a combination of acupuncture and movement therapy.

- In all cases of Type 1 treatment, needles were inserted into the affected area, and there were cases in which movement therapy was administered with needles inserted at the opposite side of LI4 [30] or with additional administration of scalp acupuncture [31]. In Type 2 studies, in which acupuncture was administered at distal acupoints and movement was applied without needle retention, the acupuncture points used in the selected studies included ST38 [32] on the opposite side, Jutong (near ST35 and EX-LE5) [33], ST38 and BL57 [34], and GB34 [35]. There were also cases of acupuncture points at SI 3 [36] on the affected side, around the foot [37], and in the upper limbs [38]. For acupoints at both sides or in the central area, bilateral GV16, LR2, LI11 [27,39], EX-HN3 [40], Yaotong [41], and scalp [42,43] points were used. In the case of studies of acupuncture points at the LR5 [44] and GV26 points [45], the side was not specified, and one study set the points as Yaotong plus left LI3, regardless of the affected side [46].

- Movement therapy was administered to the affected area during needle retention. Regarding the type of movement, no studies applied passive movements alone; most studies performed active movements [24,30–37,39,40–42,44–47], and there were some cases in which active and passive movements were performed [27,38,43,48,49]. For exercises during needling, bending and stretching exercises of the joints were the main types of exercises; there were three studies with neck exercises (cervical joint) [24,36,44], one with TMD joint movement [30], two studies with shoulder joint movement [32,34], three studies with upper limb exercises other than shoulder joint exercises, e.g., wrist or elbow exercises [33,35,49], three studies with lower limb exercises including hip joint or knee joint exercises [31,38,48], and three studies with lumbar joint movement [40,44,47]. Moreover, there were studies that applied lower extremity exercises, such as quadriceps muscle training or squats [37,41,42], and there were also studies with whole-body exercises, such as upper and lower limb exercises or walking [27,39,43].

- When classified based on the physician’s workload and risk of the procedure administered, in Type 1 studies, there were three cases of high workload [24,49,50] and two cases of moderate workload [30,31]. In Type 2 studies, there were four cases of high workload [27,38,39,43], and 13 cases of moderate workload [32–37,40–42,44–47]. Regarding risk, in Type 1 studies, there were five cases of moderate risk [24,30,31,49,50], and in Type 2 studies, there were three cases of moderate risk [37,39,40], and 14 cases of low risk [32–36,38,40–47].

- 4. Comparators

- Apart from five case series studies without comparators, when examining the comparators used in the selected studies, three studies compared the “combination of acupuncture and movement therapy” with IKM treatment [24,27,48]. All of these studies compared the effectiveness of the add-on-type treatment in which the “combination of acupuncture and movement therapy” was added to IKM treatment with that of IKM treatment alone. Four studies used conventional acupuncture as a comparator [34,36,41,44], and some compared the “combination of acupuncture and movement therapy” with injections or medication [33,39,47]. The studies that used conventional rehabilitation training as the comparator accounted for the largest number (n = 5), among which there were studies that used conventional rehabilitation training alone as the comparator, and also cases of using combined treatment as the comparator, such as a combination of conventional rehabilitation training and acupuncture or movement therapy [49], or a combination of rehabilitation training with lower-limb intelligent feedback training [42].

- 5. Effectiveness

- The effectiveness of the combination of acupuncture and movement therapy was evaluated using various outcome measures such as pain outcome depicted on a scale, functional disability outcome, and range of movement (ROM), and most studies showed significant improvement with the combination of acupuncture and movement therapy compared with the outcomes of comparators. In particular, pain outcomes (as depicted on a scale) showed a significant effect of improvement compared with comparators in 11 studies [24,32,34,37–41,46,48], and seven studies demonstrated significant improvement in terms of functional disability [32,37–41,46], five studies showed improvement in ROM [24,34,41,46,47], five studies for quality of life [32,34,42,43,49], two studies for stiffness [42,49], and three studies for motor function [42,43,49].

- In contrast, another study reported that although the outcomes in terms of the Numeric Rating Scale score, Oswestry Disability Index, and EuroQol-5 dimensions 5 level score showed significant improvement after treatment in the intervention group, the difference in the outcomes with comparators was not significant. Another study reported no significant difference in the effective rate between the two groups [44]. In addition, a data mining study [36] recommended conventional acupuncture therapy for patients with a high general health status before treatment, and a combination of acupuncture and MSAT for patients with a mild-to-moderate decline in physiological function.

- In the five case series studies, only the efficacy rate was measured without other outcome measures, and most studies showed a high efficacy rate (> 90%).

- 6. Adverse events

- Adverse events were reported in five studies. Noh et al [48] reported eight adverse events in the IKM group and four adverse events in the MSAT group, most of which were mild gastrointestinal symptoms. Kim et al [24] reported adverse events in 13 patients in the MSAT group and 7 patients in the IKM treatment group. Likewise, most of the adverse events were gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea or nausea. Apart from one case where antihistamines were taken because of an itchy sensation, all adverse events were mild, and no special treatment was required.

- Shi et al [32] reported three cases of adverse events (hematoma, bleeding, and needling pain) in the MSAT group, and Lin et al [40] reported one event in a patient with dizziness. Zhang et al [46] reported one case of subcutaneous hematoma, one case of blood stasis around the needling point in the intervention group, and two cases of anorexia and nausea in the medication group.

- 7. Mechanisms

- Although the mechanism underlying MSAT has not yet been elucidated, several studies have reported possible mechanisms for the combination of acupuncture and movement therapy. The most frequently described mechanism is that MSAT ends the negative cycle of pain. Patients with severe pain may be inclined to avoid movement because of fear of pain and negative perceptions about pain, and such avoidance and fear will create a vicious cycle of pain that leads to functional disability and pain. During treatment, the strong simulation of acupuncture points stimulates internal activity of the central nervous system, thereby triggering “diffuse noxious inhibitory controls” and increasing the secretion of endorphins, resulting in reduced pain. Thus, if a patient feels less pain and gains mobility through the combination of acupuncture and movement therapy, the treatment will then create a positive cycle, which will lead to maximized therapeutic effects [24,32,48]. Additionally, movement of the affected area during needling may enhance pain relief with acupuncture. These effects overlap and may act synergistically to increase the cure rate while distracting the patient, alleviating their fear of acupuncture, and relieving their pain during needle insertion [33].

- Regarding scalp acupuncture and exercise therapy, Gao et al [43] reported that the brain is an important organ for regulating qi, acupoints, and organs, and the head is the basic treatment point for cerebral palsy. In scalp acupuncture, various external stimuli are transmitted to the cortex of the brain, which increases cerebral blood flow, and improves the metabolism of brain cells to promote the recovery of brain tissue, thereby improving nerve and motor function. Shi et al [31] also reported that scalp acupuncture contributes to the reconstruction of nerve function in the brain, and that its combination with movement therapy promotes a patient’s self-regulating ability, thereby facilitating improvement in spasticity.

- There are also explanations that focus on the mechanical effects of movement. Xu et al [34] reported that strong acupuncture stimulation can produce an immediate analgesic effect over an extensive area, and that the movement of the shoulder joint itself enhances the long-term effect of acupuncture in pain relief, loosening tissue adhesions, and increasing the range of motion of the joint. Liu et al [47] explained that along with exploiting the advantages of the immediate analgesic effect of strong acupuncture stimulation, lumbar movement will address the discordance in the lumbar spinal joint, and promote blood flow and metabolism to improve spasticity and relieve pain. Similarly, Lin et al [40] reported that when active exercise is combined with needling of acupuncture, micro-displacement of spinal joints and fasciae can be controlled, preventing adhesion between the muscles and connective tissues, and improving endogenous facet joint disorders and exogenous kinetic structure imbalances.

Results

- The combination of acupuncture and movement therapy is a relatively novel treatment, and the treatment method is growing in popularity in Korea and China. In particular, MSAT is increasingly being used in Korea, and treatment with the same name is also being administered in China. However, general matters such as the concept of MSAT have yet to be established. In this review, 22 clinical studies were selected from a PubMed search, all of which used a combination of acupuncture and movement therapy. Detailed discussions are presented in terms of general characteristics, the number of participants, type of intervention, comparators, effectiveness, adverse events, and mechanisms of MSAT.

- The 22 studies were classified according to Type 1 or Type 2 treatment. In Type 1 treatment, after needling on the affected side, the area with the needle retained was subjected to active or passive movement. In Type 2 treatment, needling was administered at distal acupoints, which are far from the affected area, and the affected area, without needle retention, was subjected to active/passive movement. In most cases, active movements were performed for movement therapy, and there were cases in which active and passive movements were combined.

- In Korea, acupuncture is a treatment covered by national health insurance, and the Korean health insurance fee system is a fee-for-service based on the resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS). Accordingly, the health insurance fee for a specific service is determined based on the RBRVS for the service, which is determined by the physician’s time and effort for the service, risk of treatment, and amount of resources such as equipment. Thus, in addition to the traditional general classification of MSAT according to local/distal acupoints, a new classification reflecting the workload of physicians, and the risk of treatment (which are the determinants of RBRVS), is needed.

- Intervention in this review was classified according to the physician’s workload and risk of the procedure. In the case of Type 1 treatment, all cases were classified as “high” risk of procedure. On the contrary, in the case of Type 2 treatment, depending on the type of movement therapy, except three cases of “high” risk, the remaining cases were classified as “low” risk of procedure. On the basis of a physician’s workload, depending on the status of active/passive movement, seven cases were classified as “high” workload (Type 1, three; Type 2, four) and 15 cases were classified as “moderate” workload (Type 1, two; Type 2, 13). Therefore, for treatments that required direct movement of the joint area with the needle retained, or even if no direct movement was involved, and for those that may cause direct stimulation to the area of needle insertion due to movement such as walking with a needle inserted at a point in the foot, a higher RBRVS score than for treatments with no such risks needs to be applied.

- Considering the types of conditions/diseases for which a combination of acupuncture and movement therapy was administered, musculoskeletal pain, such as LBP, radiating leg pain, neck pain, knee pain, shoulder pain, tennis elbow, and TMD were the main types of illness. In most studies, MSAT showed significant improvements in the pain outcome as depicted on a scale, functional disability outcome, and ROM as compared with the comparators used in a particular study. Most case studies without comparators showed high efficacy rates (> 90%). Therefore, this review’s findings determined that a combination of acupuncture and movement therapy can be an effective treatment, especially for those with musculoskeletal pain. However, there have been very few high-quality RCTs on this topic, hence, further studies are required.

- In terms of safety, only five of 22 studies reported adverse events, indicating that there have been very limited related studies on this outcome. However, most of the reported adverse events were mild and disappeared without additional treatment. In addition, the patients mainly had gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea and diarrhea, which are judged to be side effects of medication rather than MSAT. Adverse events judged to have a causal relationship with MSAT included mild hematoma, bleeding, and needling pain. However, the number of reported cases was still very small, and treatments that involved movement at the needling point were classified as “moderate” risk. Further studies on the adverse events are needed.

- The mechanism of MSAT is yet to be elucidated, but several studies have discussed it. For the type of MSAT treatment that involves movement of the needling points after needle insertion in the affected area, the most commonly discussed mechanism is that MSAT discontinues the negative cycle of pain. Furthermore, the mechanism of the combined effects, such as the effect of promoting self-regulating ability through a combination of scalp acupuncture and movement therapy, strong and immediate analgesic effect of acupuncture, and the role of joint movement in preventing connective tissue adhesion, have been discussed. Future research is required to further investigate these mechanisms.

- In Korea, there is a treatment called dong-qi acupuncture that combines acupuncture and movement therapy in addition to MSAT. However, little research has been performed on this treatment, and it does not seem to be widely used. Therefore, dong-qi acupuncture was not included in this review because it was not indexed in PubMed. The dong-qi method is frequently used for paralytic hemiplegia and musculoskeletal disorders [51–53]. Unlike most MSATs, which move the acupuncture treatment site, dong-qi acupuncture moves the non-acupuncture treatment site with distal acupoints. Therefore, the risk of dong-qi acupuncture can be classified as “low.” If additional literature reviews are performed and discussion of other similar acupuncture methods are conducted, a more in-depth discussion of MSAT will be possible.

Discussion

- MSAT refers to a treatment method in which acupuncture and movement therapy are administered concurrently rather than sequentially, and active/passive movements are applied to a patient under the assistance/supervision of a physician with the needle retained. MSAT can serve as an effective treatment for patients with musculoskeletal pain. However, few related studies have been published, different treatment methods are available according to the type of acupuncture and movement therapy, and various words are used which may cause confusion. Moreover, in the case of MSAT, even among studies using the same name for the treatment, different classifications are used in terms of the acupuncture points, type of movement, and risks involved in the procedure. Therefore, the establishment of a classification system and a clear concept of MSAT based on more recent considerations, such as physicians’ workload and the risk of the procedure is required in addition to, further high-quality RCTs for MSAT.

Conclusion

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: IHH. Methodology: YJL. Formal analysis: DK. Investigation: DK. Writing original draft: DK. Writing - review and editing: IHH and YJL.

-

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve any human or animal experiments.

-

Funding

None

-

Data Availability

All relevant data are included in this manuscript.

Article information

| Type | 1st author (y) [ref] | Country of origin | Study design | Participants’ condition, number of participants (intervention/control) | Type of intervention | Comparator | Outcome | Main results | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Noh (2021) [50] | Korea | Pros, Obs | LBP or radiating pain, 40 (20/20) | IKM/MSAT | IKM | NRS, ODI, VAS, EQ-5D-5L |

Diff between two groups after tx NRS for LBP: −1.2 (−2.22, −0.19), p < 0.05 NRS for RP: −0.97 (−1.89, −0.06) p < 0.05 |

Tx (n = 4), ctrl (n = 8) Severity: mild Sx: gi sx (heartburn, abdominal discomfort) |

| Kim (2020) [24] | Korea | RCT | Neck pain, 100 (50/50) | IKM/MSAT | IKM | NRS, VAS, NDI, ROM, EQ-5D-5L, PGIC |

Diff between two groups after tx NRS: −1.05 (−1.57, −0.53), p < 0.05 ROM (Flexion): 5.55 (2.80, 8.31), p < 0.05 ROM (Extension): 6.60 (2.97, 10.23), p < 0.05 |

Tx (n = 13), ctrl (n = 7) Severity: mild except 1 Sx: diarrhea (n = 12), nausea or heartburn (n = 3), itching and rash (n = 4), dizziness (n = 1). | |

| Wang (2020) [49] | China | RCT | Post-stoke, 105 (35/35/35) | C_rehb/Acu + KT | C_rehb/1. Acu only 2. KT only | MAS, ROM FMA, BI |

Diff before and after tx in the tx group MAS: 1.41 ± 0.49 (ctrl 0.82 ± 0.43, 0.74 ± 0.28) FMA: 9.91 ± 3.01 (ctrl 6.45 ± 1.91, 5.85 ± 1.79) ADL: 28.24 ± 5.59 (ctrl 19.70 ± 7.60, 19.85 ± 6.80) |

Not specified | |

| Wang (2015) [30] | China | Case series | TMD, 15 | Floating acu + jaw movement | None | - |

Recovery: 10, Significant effect: 2 Effect: 2, Invalid: 1 |

Not specified | |

| Shi (2015) [31] | China | Case series | Post-stoke, 30 | Exercise acu | None | - |

Recovery: 5, Significant effect: 9 Effect: 12, Invalid: 4, Effective rate: 86.7% |

Not specified | |

| 2 | Shi (2018) [32] | China | RCT | Shoulder pain, 164 (41/41/41/41) | Acu/MSAT | 1. MSAT + mCAT 2. mMSAT + CAT 3. mMSAT + mCAT | VAS, CMS, SF-36, Treatment Credibility Scale |

VAS at the 18-wk follow-up: MSAT 25.3 (24.1)/mMSAT 35.0 (25.0), p = 0.013 CAT 29.6 (25.2)/mCAT 30.7 (24.7), p = 0.78 CMS at the 18-wk follow-up: MSAT 79.9 (15.5)/mMSAT 73.3 (16.7), p = 0.010 CAT 75.3 (17.5)/mCAT 78.0 (15.1), p = 0.29 |

Tx (n = 6), ctrl (n = 6) Sx: small hematoma (n = 6), discomfort at needle insertion (n = 4), needling pain (n = 2) |

| Lyu (2022) [36] | China | RCT | Neck pain, 76 (39/39) | Acu/MSAT | Acu | SF-36, pain pressure threshold | MSAT can be effective when the physical function score is 41.7–68.7 in the tx group, and CAT can be effective when the general health score is 56.09–66.09 in the ctrl group | Not specified | |

| Park (2022) [27] | Korea | Retro | LBP or radiating pain, 152 (28/124) | IKM/MSAT (H-MSAT or T-MSAT) | IKM | NRS for LBP NRS for RP, ODI, EQ-5D-5L |

Outcome changes in the MSAT group after tx NRS for LBP: 5.71 ± 1.58 → 2.57 (1.96–3.19) NRS for RP: 6.14 ± 1.35 → 2.72 (2.02–3.42) ODI: 49.69 ± 18.16 → 27.46 (22.26–32.66) EQ-5D: 0.54 ± 0.20 → 0.75 (0.71–0.80) |

Not specified | |

| Gao (2019) [43] | China | RCT | Cerebral palsy, 52 (23/29) | C_rehb/Scalp acu + exercise | C_rehb | GMFM-88, ADL |

Rate of change before and after tx GMFM-88: Tx 16.84%, ctrl 12.98% (p < 0.05) ADL: Tx 26.55%, ctrl 25.59%, (p < 0.05) |

Not specified | |

| Shin (2013) [39] | Korea | RCT | LBP or radiating pain, 58 (29/29) | MSAT | Intramuscular injection of NSAIDS (diclofenac) | NRS for LBP, ODI, |

Diff between the two groups 30 min after tx NRS for LBP: 3.12 (2.26, 3.98), p < 0.0001 NRS for RP: 0.97 (0.22, 1.71), p = 0.0137 ODI: 32.95 (26.88, 39.03), p < 0.0001 |

Not specified | |

| Xu (2018) [34] | China | RCT | Shoulder pain, 60 (30/30) | Acu + exercise | Acu | VAS, Melle, ADL |

Outcomes after tx VAS: Tx 2.30 ± 1.12, ctrl 4.53 ± 1.36 (p < 0.05) Melle: Tx 3.50 ± 1.91, ctrl 8.40 ± 2.47 (p < 0.05) ADL: Tx 12.17 ± 3.24, ctrl 21.50 ± 1.74 (p < 0.05) |

Not specified | |

| 2 | Liu (2017) [47] | China | RCT | LBP or radiating pain, 46 (26/20) | Acu/acu + movement | Oral adm of loxoprofen sodium | ROM, VAS, PPI |

Compared to the ctrl group, the tx group showed significantly improved lumbar ROM and VAS after tx (values not specified) Recovery rate: Tx 6 (30%), ctrl 14 (53.8%) |

Not specified |

| Lin (2016) [40] | China | RCT | LBP or radiating pain, 60 (15/15/15/15) | Acu-movement therapy | 1. Sham acu-movement 2. CAT 3. PT | VAS, RMQ |

Outcomes 24 h after tx VAS: Tx 15 ± 3, ctrl 32 ± 6, 25 ± 4, 31 ± 8, p < 0.05 RMQ: Tx 4.2 ± 1.0, ctrl 7.8 ± 1.4, 6.6 ± 1.6, 7.2 ± 2.2, p < 0.05 |

AM (n = 1) Sx: dizziness (n = 1) |

|

| Zhang (2022) [46] | China | RCT | LBP or radiating pain, 160 (40/40/40/40) | Dynamic qi acu |

A: Dq-a (10 min) B: Dq-a (20 min) C: Dq-a (30 min) Med: celecoxib |

NRS, ROM, ODI |

Diff before and after tx (A, B, C, and medication) NRS: 3 (2), 3 (2), 3 (2), 2 (2) ROM: 1 (1), 1.5 (1), 1 (1.75), 0 (1) ODI: 11.11 (4.44), 16.67 (7.22), 16.67 (6.67), 7.78 (3.38) Effective rate: 94.4%, 94.7%, 97.2%, 79.4% |

A (n = 0) B (n = 1, hematoma) C (n = 1, hematoma) Medication (n = 2, nausea, anorexia) |

|

| Hong (2016) [33] | China | Case series | Tennis elbow, 160 | Exercise-acu | None | - |

Recovery: 85, significant effective: 49 Invalid: 26, effective rate: 83.7% |

Not specified | |

| Luo (2010) [44] | China | Pros, Obs | Neck pain, 122 (57/65) | Acu + movement therapy | Acupuncture | Effective rate: Tx 98.24%, ctrl 96.9%, p > 0.05 | Not specified | ||

| Qu (2019) [38] | China | Pros, Obs | Knee pain, 51 (17/17/17) | C-rehb/Exercise acu | 1. C_rehb/osteopathy 2. C_rehb | WOMAC, ROM |

WOMAC after tx TX 47.88 ± 5.94, ctrl 45.11 ± 6.16, 54.19 ± 4.65, p = 0.000 Pain score of the WOMAC Tx 8.90 ± 2.19, ctrl 11.98 ± 2.66, 10.66 ± 2.75, p = 0.004 |

Not specified | |

| Luo (2017) [37] | China | RCT | Knee pain, 71 (36/35) | C_rehb/Shu-acu | C_rehb | JOA, VAS |

Outcome after tx JOA: Tx 82.92 ± 7.48, ctrl 68.93 ± 8.85, p < 0.05 VAS: Tx 0.87 ± 0.80, ctrl 2.61 ± 1.19, p < 0.05 Effective rate: Tx 91.7%, ctrl 80.0%, p < 0.05 |

Not specified | |

| Fu (2022) [41] | China | Retro | LBP or radiating pain, 71 (36/35) | Balanced acu/manipulation. | Acu | VAS, RMDQ, ROM, JOA | Compared to the ctrl group, the tx group showed significantly improved VAS score, RMDQ, JOA score, and lumbar ROM (values not specified) | Not specified | |

| Xie (2012) [35] | China | Case series | Tennis elbow, 39 | Exercise acu | None |

Recovery: 29, effect: 9 Invalid: 1, effective rate: 97.4% |

Not specified | ||

| Sun (2014) [45] | China | Case series | LBP or radiating pain, 26 | Acu + movement therapy | None | Recovery: 14, 53.8%, significant effect: 10, 38.5%, Effect: 2, 7.7%, invalid: 0, 0% | Not specified | ||

| Zhang (2021) [42] | China | RCT | Post-stroke, 154 | C_rehb/Scalp acu + LLIFT | C_rehb/LLIFT | Brunnstrom stage, MAS, 6MW test result, BBS, mBI, plantar pressure |

Brunnstrom stage: Proportions of stages 5 and 6 after tx Tx 30%, ctrl: 15% 6MWT result: Tx 184.92 ± 27.24, ctrl 144.51 ± 30.16 BBS: Tx 45.44 ± 4.09, ctrl 39.53 ± 7.36 MBI: Tx 52.28 ± 5.78, ctrl 36.97 ± 6.49 |

Not specified |

Acu = acupuncture; ADL = activities of daily living; BBS = Berg balance scale; BI = Barthel index; CAT = conventional acupuncture treatment; CMS = Constant-Murley score; Ctrl = control; C_rehb = conventional rehabilitation; Diff = difference; Dq-a = dynamic qi acupuncture; EQ-5D-5L = EuroQol-5 dimensions 5 level; FMA = Fugl-Meyer Assessment; GMFM-88 = Gross Motor Function Measure-88; IKM = Integrative Korean Medicine; JOA = Japanese Orthopaedics Association; KT = kinesiotherapy; LBP = low back pain; LLIFT = lower-limb intelligent feedback training; MAS = Modified Ashworth Scale; mBI = modified Barthel Index; mCAT = minimize conventional acupuncture treatment; mMSAT = minimize motion style acupuncture treatment; MSAT = motion style acupuncture treatment; NDI = neck disability index; NRS = numeric rating scale; NSAIDS = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; Obs = observational; ODI = Oswestry disability index; PGIC = patient’s global impression of change; PPI = present pain intensity; Pros = prospective; PT = physical therapy; RCT = randomized controlled trial; Retro = retrospective; RMDQ = Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire; RMQ = Roland Morris Questionnaire; ROM = range of motion; RP = radiating pain; SF-36 = Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire; Sx = symptoms; TMD = temporomandibular disorder; Tx = treatment; VAS = visual analog scale; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index; 6MW = 6-minute walk test.

| Type | 1st author (y) [ref] | Type of intervention | Acupuncture points | Movements (type of movement, body part) | Duration of the treatment sessions | Workload | Risk of procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Noh (2021) [50] | IKM/MSAT | Affected side, local, BL54, GB30, BL23, BL24,245,26,31,32 | Passive/active, hip joint | 10–20 min of MSAT was administered during hospitalization | High | Moderate |

| Kim (2020) [24] | IKM/MSAT | Both sides, local, both upper trapezius | Active, cervical joint | 3 times (Days 2, 3 and 4 of hospitalization). 10 min | High | Moderate | |

| Wang (2020) [49] | C_rehb/Acu + KT | Affected side, local, penetrating LI4, SI3, penetrating PC06, TE5 | Passive/active, wrist, metacarpophalangeal, interphalangeal joints | Once/d ×6 d/wk ×2 wk/course ×2 courses 30 min per session | High | Moderate | |

| Wang (2015) [30] | Floating acu + jaw movement | Opposite/affected, distal/local, the opposite side of LI4 + affected area (points of pain during jaw movement for opening the mouth) | Active, temporomandibular joint | Once/d ×10 d/course ×2 courses, 30-min needle retention | Moderate | Moderate | |

| Shi (2015) [31] | Exercise acu | Both/affected side, distal/local, scalp acu + lower limb of the affected side | Active, hip joint, knee joint, ankle joint | Once/d ×2 wk, 30 min of needle retention after exercise | Moderate | Moderate | |

| 2 | Shi (2018) [32] | Acu/MSAT | Opposite side, distal ST38 | Active, shoulder joint | Twice/wk ×6 wk, 20 min | Moderate | Low |

| Lyu (2022) [36] | Acu/MSAT | Affected side, distal SI3 | Active, cervical joint | Twice/wk ×5 wk ×2 courses, 20-min needle retention followed by 5-min of MSAT | Moderate | Low | |

| Park (2022) [27] | IKM/MSAT (H-MSAT or T-MSAT) | Both sides, distal GV16, LR2, LI11 | Active/passive, walking, physician-assisted (H-MSAT), device-assisted (T-MSAT). A patient is asked to walk with the assistance of the physicians on both sides. Then, the medical staff gradually stops supporting the patient. For T-MSAT, traction is used to help patients walk instead of physician assistants. |

H-MSAT: 2.75 ± 2.74 (n = 16) T-MSAT: 8.50 ± 9.17 (n = 16) 10–20 min per session |

High | Moderate | |

| Gao (2019) [43] | C_rehb/Scalp acu + exercise | Both sides, scalp acu (motor area, balance zone, foot motor sensory area, sensory area, language area) | Active/passive, limb exercise, anti-gravity movement of the affected limb, horizontal movement, flexion movement of the joint | Once/d ×5 d/wk ×3 mo. 1 h | High | Low | |

| Shin (2013) [39] | MSAT | Both sides, distal GV16, LR2, LI11 | Active/passive, walking | Once, 20 min | High | Moderate | |

| Xu (2018) [34] | Acu + exercise | Opposite side, distal ST38, BL57 | Active, shoulder joint | Five times, every 2 d + 2 sets 5-min exercise during 20-min needle retention | Moderate | Low | |

| Liu (2017) [47] | Acu/Acu + movement | Both sides, distal/local Yaotong (above Yintang, EX-HN3) + local Ashi-points (lumbar) | Active, lumbar joint, Ashi-points acu after acu (Yaotong) + movement therapy | Three times/wk ×1 wk 20 min + extra | Moderate | Low | |

| Lin (2016) [40] | Acu + movement therapy | Both sides, distal Yintang (EX-HN3) | Active, lumbar joints | Once, 20 min | Moderate | Low | |

| 2 | Zhang (2022) [46] | Dynamic qi acu | Both sides, distal Yaotong + left LI3 | Active, lumbar joints | 5 d | Moderate | Low |

| Hong (2016) [33] | Exercise acu | Opposite side, distal Jutong (near ST35 and EX-LE5) | Active, elbow joints | Once every 2 d ×5 times ×3 courses, 30–45 min, 6 mo follow-up | Moderate | Low | |

| Luo (2010) [44] | Acu + movement therapy | Side not specified, distal LR5 | Active, cervical joints | Daily for 10 d, 30 min | Moderate | Low | |

| Qu (2019) [38] | C-rehb/Exercise acu | Affected side, distal LI4, PE6, LI11 | Active/passive, knee joints | Once daily, 4 wk, 20 min. | High | Low | |

| Luo (2017) [37] | C_rehb/Shu-acu | Affected side, distal BL66, BL65, ST44, ST43, ST41, GB41, SP2, SP3, LR2, LR3 | Active, quadriceps muscle training | Once daily, 30-min needle retention, treatment for 6 d in a row, followed by 1 d of a break and then by 8 wk of treatment | Moderate | Moderate | |

| Fu (2022) [41] | Balanced acu/Manipulation | Both sides, distal Yaotong | Active, lower extremity exercises such as squats and sit to stand | Daily, 5 d (No explicit mention of duration) | Moderate | Low | |

| Xie (2012) [35] | Exercise acu | Opposite side, distal GB34 | Active, elbow joint | Once/d 10 d ×2 courses 30–45 min | Moderate | Low | |

| Sun (2014) [45] | Acu + movement therapy | Side not specified, distal GV26 | Active, antagonistic movement (instructing the sacrum to hold motion that causes pain) | Once/d ×6 d/wk ×2 wk 30 min | Moderate | Low | |

| Zhang (2021) [42] | C_rehb/Scalp acu + LLIFT | Both sides, distal Scalp acu | Active, lower extremity exercise | Once/d ×6 d/wk ×8 wk 40 min | Moderate | Low |

- [1] Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice. Ann Intern Med 2002;136(5):374−83.ArticlePubMed

- [2] Vickers A, Zollman C. ABC of complementary medicine: acupuncture. BMJ 1999;319(7215):973−6.ArticlePubMedPMC

- [3] Madsen MV, Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A. Acupuncture treatment for pain: systematic review of randomised clinical trials with acupuncture, placebo acupuncture, and no acupuncture groups. BMJ 2009;338:a3115. ArticlePubMedPMC

- [4] Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain Mechanisms: A New Theory: A gate control system modulates sensory input from the skin before it evokes pain perception and response. Science 1965;150(3699):971−9.ArticlePubMed

- [5] Zhao Z-Q. Neural mechanism underlying acupuncture analgesia. Prog Neurobiol 2008;85(4):355−75.ArticlePubMed

- [6] Cabýoglu MT, Ergene N, Tan U. The mechanism of acupuncture and clinical applications. Int J Neurosci 2006;116(2):115−25.ArticlePubMed

- [7] Hsu E. Innovations in acumoxa: acupuncture analgesia, scalp and ear acupuncture in the People’s Republic of China. Soc Sci Med 1996;42(3):421−30.ArticlePubMed

- [8] Melzack R, Stillwell DM, Fox EJ. Trigger points and acupuncture points for pain: correlations and implications. Pain 1977;3(1):3−23.ArticlePubMed

- [9] Napadow V, Makris N, Liu J, Kettner NW, Kwong KK, Hui KK. Effects of electroacupuncture versus manual acupuncture on the human brain as measured by fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 2005;24(3):193−205.ArticlePubMedPMC

- [10] Hwang IK, Chung JY, Yoo DY, Yi SS, Youn HY, Seong JK, et al. Comparing the effects of acupuncture and electroacupuncture at Zusanli and Baihui on cell proliferation and neuroblast differentiation in the rat hippocampus. J Vet Med Sci 2010;72(3):279−84.ArticlePubMed

- [11] Tsui P, Leung MC. Comparison of the effectiveness between manual acupuncture and electro-acupuncture on patients with tennis elbow. Acupunct Electrother Res 2002;27(2):107−17.ArticlePubMed

- [12] Yue Z-H, Li L, Chang X-R, Jiang J-M, Chen L-L, Zhu X-S. Comparative study on effects between electroacupuncture and acupuncture for spastic paralysis after stroke. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2012;32(7):582−6. [in Chinese].PubMed

- [13] Wang T-Q, Li Y-T, Wang L-Q, Shi G-X, Tu J-F, Yang J-W, et al. Electroacupuncture versus manual acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Acupunct Med 2020;38(5):291−300.ArticlePubMedPDF

- [14] Aranha MF, Müller CE, Gavião MB. Pain intensity and cervical range of motion in women with myofascial pain treated with acupuncture and electroacupuncture: a double-blinded, randomized clinical trial. Braz J Phys Ther 2014;19(1):34−43.ArticlePubMedPMC

- [15] Ouyang B-S, Che J-L, Gao J, Zhang Y, Li J, Yang H-Z, et al. Effects of electroacupuncture and simple acupuncture on changes of IL-1, IL-4, IL-6 and IL-10 in peripheral blood and joint fluid in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2010;30(10):840−4. [in Chinese].PubMed

- [16] Seo Y, Lee I-S, Jung W-M, Ryu H-S, Lim J, Ryu Y-H, et al. Motion patterns in acupuncture needle manipulation. Acupunct Med 2014;32(5):394−9.ArticlePubMedPDF

- [17] Shi G-X, Yang X-M, Liu C-Z, Wang L-P. Factors contributing to therapeutic effects evaluated in acupuncture clinical trials. Trials 2012;13:42. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [18] Yoon D-E, Lee I-S, Chae Y. Comparison of the acupuncture manipulation properties of traditional East Asian medicine and Western medical acupuncture. Integr Med Res 2022;11(4):100893. ArticlePubMedPMC

- [19] Huang T, Huang X, Zhang W, Jia S, Cheng X, Litscher G. The influence of different acupuncture manipulations on the skin temperature of an acupoint. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:905852. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [20] Fang J, Krings T, Weidemann J, Meister I, Thron A. Functional MRI in healthy subjects during acupuncture: different effects of needle rotation in real and false acupoints. Neuroradiology 2004;46:359−62.ArticlePubMedPDF

- [21] Kim GH, Yeom M, Yin CS, Lee H, Shim I, Hong MS, et al. Acupuncture manipulation enhances anti-nociceptive effect on formalin-induced pain in rats. Neurol Res 2010;32:Suppl 1. 92−5.ArticlePubMed

- [22] Hong S, Ding S, Wu F, Xi Q, Li Q, Liu Y, et al. Strong manual acupuncture manipulation could better inhibit spike frequency of the dorsal horn neurons in rats with acute visceral nociception. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015;2015:675437. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [23] Shin J, Boone W, Kim P, So C. Acute and long term benefits of motion style treatment (MST): two case reports. Int J Clin Acupunct 2007;16(2):85−92. https://m.jaseng.org/research/scholarship/thesis_view.do?idx=175.

- [24] Kim D, Park K-S, Lee J-H, Ryu W-H, Moon H, Park J, et al. Intensive motion style acupuncture treatment (MSAT) is effective for patients with acute whiplash injury: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med 2020;9(7):2079. ArticlePubMedPMC

- [25] Kim D, Lee YJ, Park KS, Kim S, Seo J-Y, Cho HW, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of motion style acupuncture treatment (MSAT) for acute neck pain: A multi-center randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2020;99(44):e22871. PubMedPMC

- [26] Shin J-S, Ha I-H, Lee T-G, Choi Y, Park B-Y, Kim M, et al. Motion style acupuncture treatment (MSAT) for acute low back pain with severe disability: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial protocol. BMC Complement Altern Med 2011;11:127. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [27] Edited by Park M-J, Jin S-R, Kim E-S, Lee H-S, Hwang K-H, Oh S-J, et al.:Long-Term Follow-Up of Intensive Integrative Treatment including Motion Style Acupuncture Treatment (MSAT) in Hospitalized Patients with Lumbar Disc Herniation: An Observational Study. Healthcare (Basel). 2022, 10(12):p 2462. ArticlePubMedPMC

- [28] Chen D. Introduction to “motion acupuncture” and target points. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2016;36(9):941−4. [in Chinese].PubMed

- [29] Chen D, Yang G, Wang F, Qi W. Motion acupuncture for therapeutic target. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2016;36(11):1177−80. [in Chinese].ArticlePubMed

- [30] Wang J, Xiang Y, Hao C. Floating acupuncture combined with jaw movement and TDP for 15 cases of temporomandibular joint disorder. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2015;35(3):232[in Chinese].PubMed

- [31] Shi G, Zheng X, Song N. Acupuncture at tendons node combined with movement for 30 cases of post-stroke spastic paralysis in lower limbs. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2015;35(3):212[in Chinese].PubMed

- [32] Shi GX, Liu BZ, Wang J, Fu QN, Sun SF, Liang RL, et al. Motion style acupuncture therapy for shoulder pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Res 2018;11:2039−50.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [33] Hong K. Knife-edge needling combined with movement for 160 cases of tennis elbow. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2016;36(3):279−80. [in Chinese].PubMed

- [34] Xu S, Zhang H, Gu Y. Acupuncture from Tiaokou (ST 38) to Chengshan (BL 57) combined with local exercise for periarthritis. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2018;38(8):815−8. [in Chinese].PubMed

- [35] Xie XJ, Lan CG, Lü JZ. Contralateral acupuncture at Yanglingquan (GB 34) combined with movement for tennis elbow. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2012;32(9):797[in Chinese].PubMed

- [36] Lyu RY, Wen ZL, Tang WC, Yang XM, Wen JL, Wang B, et al. Data mining-based detection of the clinical effect on motion style acupuncture therapy combined with conventional acupuncture therapy in chronic neck pain. Technol Health Care 2022;30(S1):521−33.ArticlePubMedPMC

- [37] Luo K, Qi T, Hou Z, Bian N, Zhao Y. Clinical research for rehabilitation training combined with modified shu-acupuncture for joint dysfunction after meniscal suture surgery. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2017;37(9):957−60. [in Chinese].PubMed

- [38] Qu XD, Zhou JJ, Zhai HW, Chen W, Cai XH. Therapeutic effect of exercise acupuncture and osteopathy on traumatic knee arthritis. Zhongguo Gu Shang 2019;32(6):493−7. [in Chinese].PubMed

- [39] Shin JS, Ha IH, Lee J, Choi Y, Kim MR, Park BY, et al. Effects of motion style acupuncture treatment in acute low back pain patients with severe disability: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, comparative effectiveness trial. Pain 2013;154(7):1030−7.ArticlePubMed

- [40] Lin R, Zhu N, Liu J, Li X, Wang Y, Zhang J, et al. Acupuncture-movement therapy for acute lumbar sprain: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Tradit Chin Med 2016;36(1):19−25.ArticlePubMed

- [41] Fu G, Liu X, Wang W, Fan N, Cao S, Liu H. Efficacy comparison of acupuncture and balanced acupuncture combined with TongduZhengji manipulation in the treatment of acute lumbar sprain. Am J Transl Res 2022;14(7):4628−37.PubMedPMC

- [42] Zhang SH, Wang YL, Zhang CX, Li QF, Liang WR, Pan XH, et al. Scalp acupuncture combined with lower-limb intelligent feedback training for lower-limb motor dysfunction after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2021;41(5):471−7. [in Chinese].PubMed

- [43] Gao J, He L, Yu X, Wang L, Chen H, Zhao B, et al. Rehabilitation with a combination of scalp acupuncture and exercise therapy in spastic cerebral palsy. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2019;35:296−300.ArticlePubMed

- [44] Luo BH, Han JX. Cervical spondylosis treated by acupuncture at Ligou (LR 5) combined with movement therapy. J Tradit Chin Med 2010;30(2):113−7.ArticlePubMed

- [45] Sun YZ, Sun YZ. Acupuncture at Shuigou (GV 26) point combined with antagonistic movement for 26 cases of coccygodynia. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2014;34(7):717[in Chinese].PubMed

- [46] Zhang YL, Chen S, Luo ZH, Chen B, Zhou T, Gu XL, et al. Clinical efficacy and time-effect relationship of dynamic qi acupuncture for acute lumbar sprain. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2022;42(12):1368−72. [in Chinese].PubMed

- [47] Liu LL, Lu J, Ma HF. Clinical Trials for Treatment of Acute Lumbar Sprain by Acupuncture Stimulation of “Yaotong” and Local Ashi-points in Combination with Patients’ Lumbar Movement. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu 2017;42(1):72−5. [in Chinese].PubMed

- [48] Noh JH, Byun DY, Han SH, Kim J, Roh JA, Kim MY. Effectiveness and safety of motion style acupuncture treatment of the pelvic joint for herniated lumbar disc with radiating pain: A prospective, observational pilot study. Explore (NY) 2022;18(2):240−9.ArticlePubMed

- [49] Wang XC, Liu T, Wang JH, Zhang JJ. Post-stroke hand spasm treated with penetrating acupuncture combined with kinesiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2020;40(1):21−5. [in Chinese].PubMed

- [50] Mira TAA, Buen MM, Borges MG, Yela DA, Benetti-Pinto CL. Systematic review and meta-analysis of complementary treatments for women with symptomatic endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2018;143(1):2−9.ArticlePDF

- [51] Kim S-H, Jeong K-S, Park S-K, Ahn H-J, Yoon H-S. The study on the effects of Dong-qi acupuncture therapy for the patient with ankle sprain. J Acupunct Res 2005;22(4):65−72. [in Korean] https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART000966981.

- [52] Youn WS, Park YJ, Park YB. Dong-qi therapy of Dong-si acupuncture to movement system impairment syndrome of lumbar spine and knee. J Acupunct Res 2013;30(1):13−22. [in Korean].Article

- [53] Lee Y-J, Jang J-H, Park S-K, Kim M-C. The Effect of Dong-gi Acupuncture (DGA) on Rehabilitation after Stroke. J Korean Med Rehabil 2005;15(2):155−67.

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Effectiveness of lumbar motion style acupuncture treatment on inpatients with acute low back pain: A pragmatic, randomized controlled trial

Oh-Bin Kwon, Dong Wook Hwang, Dong-Hyeob Kang, Sang-Joon Yoo, Do-Hoon Lee, Minjin Kwon, Seon-Woo Jang, Hyun-Woo Cho, Sang Don Kim, Kyong Sun Park, Eun-San Kim, Yoon Jae Lee, Doori Kim, In-Hyuk Ha

Complementary Therapies in Medicine.2024; 82: 103035. CrossRef - Graded exercise with motion style acupuncture therapy for a patient with failed back surgery syndrome and major depressive disorder: a case report and literature review

Do-Young Kim, In-Hyuk Ha, Ju-Yeon Kim

Frontiers in Medicine.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Effectiveness and Safety of Progressive Loading–Motion Style Acupuncture Treatment for Acute Low Back Pain after Traffic Accidents: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Seung-Yoon Hwangbo, Young-Jun Kim, Dong Guk Shin, Sang-Joon An, Hyunjin Choi, Yeonsun Lee, Yoon Jae Lee, Ju Yeon Kim, In-Hyuk Ha

Healthcare.2023; 11(22): 2939. CrossRef

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite