Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Perspect Integr Med > Volume 2(3); 2023 > Article

-

Original Article

Structural and Criterion Validity of a New 6-item Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ-6) on Patients with Chronic Lower Back Pain Receiving Integrative Medicine -

Yoon Jae Lee1

, Gyu Chan Shim2

, Gyu Chan Shim2 , Changsop Yang3

, Changsop Yang3 , Chang-Hyun Han3,4,*

, Chang-Hyun Han3,4,*

-

Perspectives on Integrative Medicine 2023;2(3):182-189.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.56986/pim.2023.10.006

Published online: October 23, 2023

1Jaseng Spine and Joint Research Institute, Jaseng Medical Foundation, Seoul, Republic of Korea

2College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

3KM Science Research Division, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, Daejeon, Republic of Korea

4Korean Convergence Medical Science, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, Daejeon, Republic of Korea

- *Corresponding author: Chang-Hyun Han, KM Science Research Division, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, Email: chhan@kiom.re.kr

©2023 Jaseng Medical Foundation

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

- 583 Views

- 17 Download

Abstract

-

Background

- Lower back pain (LBP) is a leading cause of disability worldwide. The Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) has been widely used to assess functional impairment in patients with LBP. However, its length and redundancy calls for a more concise and optimized version.

-

Methods

- We conducted a secondary analysis of data from two randomized controlled trials comparing pharmacopuncture and physical therapy for chronic LBP. We focused on 132 patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms and analyzed their baseline data to evaluate the structural validity of the RMDQ. We used R packages lavaan and semPlot for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Model fit were assessed through various indices, including comparative fit index, Tucker–Lewis index, root mean square error of approximation, and standardized root mean squared residual.

-

Results

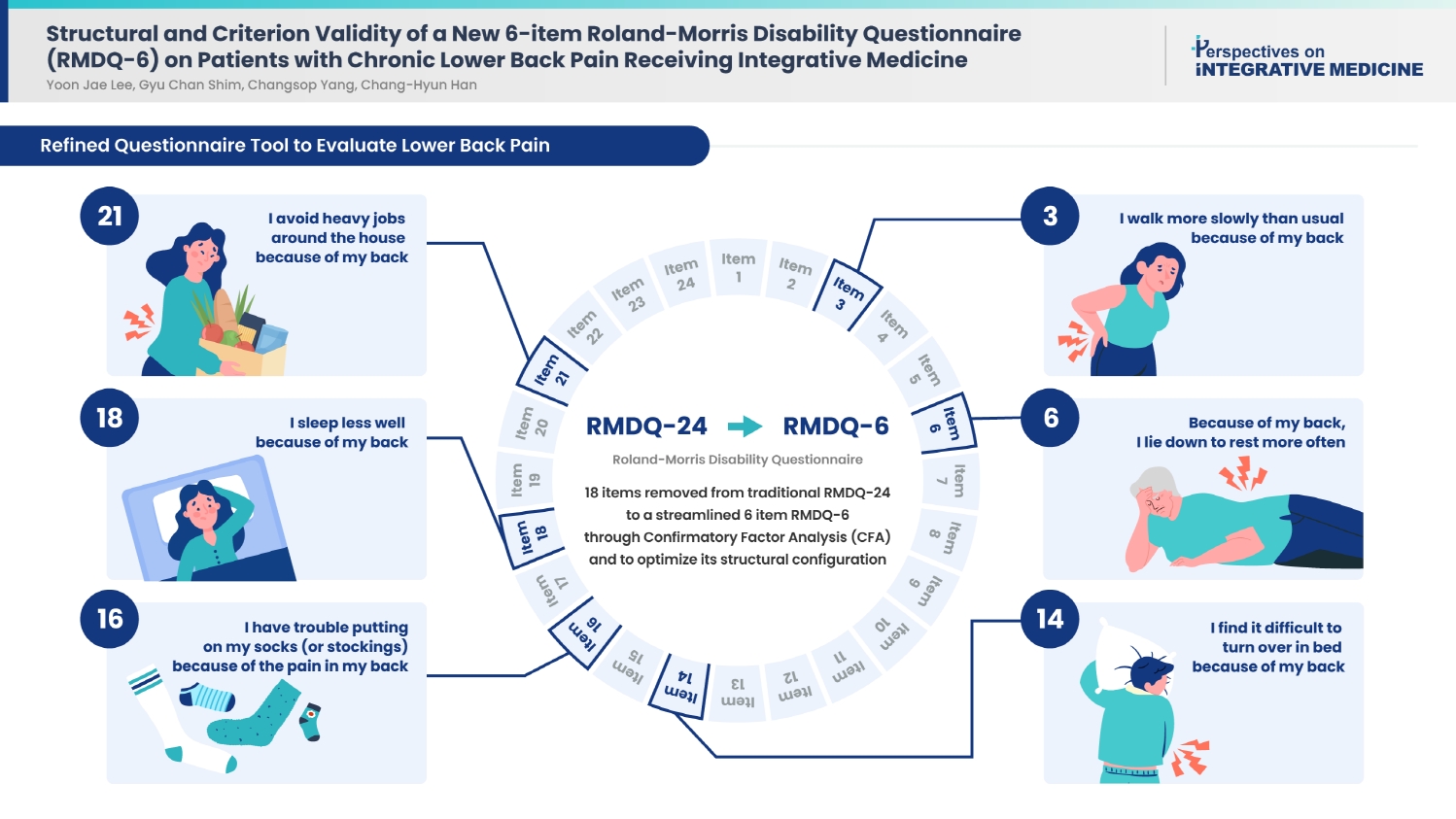

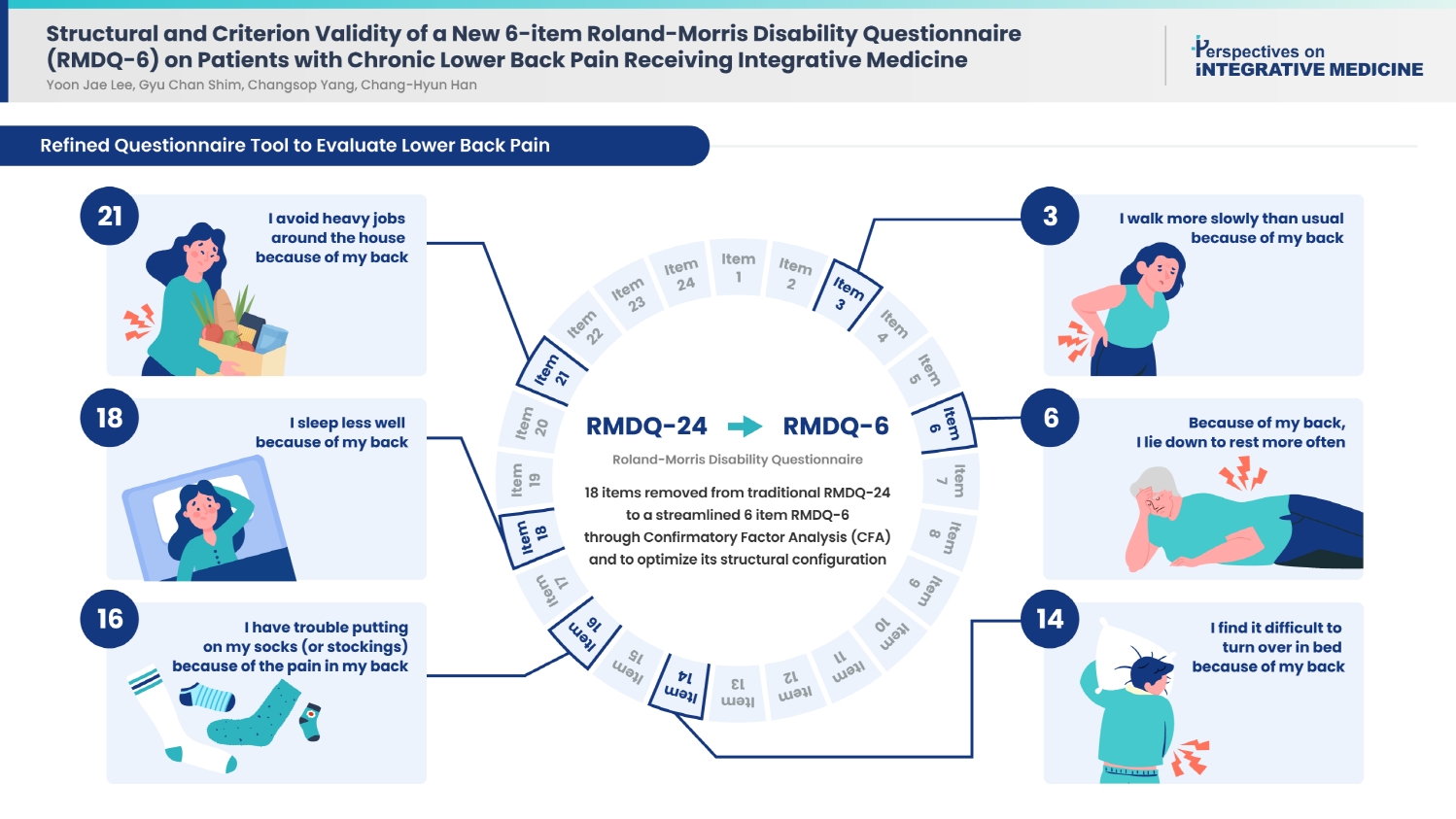

- A total of 18 items were ultimately removed to produce a streamlined 6-item structure. Our model met the fit index criteria, yielding a one-domain, 6-item RMDQ structure. While the relative indices fell slightly short of the ideal values, the RMDQ-6 derived through CFA correlated well with the original version.

-

Conclusion

- This study developed a more concise version of RMDQ through CFA to optimize its structural configuration. This concise instrument can be proposed as an efficient tool to assess the functionality of patients with LBP.

- In 2020, 619 million people worldwide suffered from lower back pain (LBP), and this is predicted to increase to 843 million cases by 2050 [1]. Furthermore, LBP ranks among the leading causes of Years Lived with Disability, with a global age-standardized rate of 843 per 100,000 people [1]. This condition progresses to a chronic state in approximately 40% of all individuals [2]. The lifetime prevalence of LBP is estimated to range from 60% to 85%, emphasizing its chronic and recurrent nature throughout an individual's lifetime [3]. Given the significant productivity losses associated with LBP [4], it is imperative to comprehensively assess both the pain intensity and the functional aspects of LBP.

- Representative tools for evaluating disabilities related to LBP include the Oswestry Disability Index [5], Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) [6], and Back Pain Functional Scale [7]. The RMDQ, in particular, exhibits superior construct validity in terms of physical function and is widely employed in clinical research. Originating in the United Kingdom in 1983 [6], the RMDQ comprises 24 items and has been translated into multiple languages since then [8–12]. However, the extensive item count of the questionnaire poses challenges for respondents in that it becomes time-consuming and presents redundancy among items. Streamlining the questionnaire is essential to reduce the response time while maintaining the quality of the acquired information; such a simplification can also mitigate response errors.

- When used to assess changes in clinical research or the progression of clinical conditions, the 24-item version of the RMDQ (RMDQ-24) may prove unwieldy and may not support frequent assessments, possibly impeding timely determination of the progress of patients’ health. Consequently, several studies have attempted to simplify the RMDQ. Stratford et al [13] proposed a modified version of the RMDQ, subsequently reducing it to 18 items. Stroud et al [14] presented an 11-item short version, whereas Friedman et al [15] proposed a concise 5-item version. Additionally, Frota et al [16] proposed a 15-item shortened version of the Brazilian version of the RMDQ. However, none of these studies conducted a factor analysis using the Korean version of the RMDQ, and no analysis, to our knowledge, has been based on research involving clinically problematic chronic moderate LBP.

- Therefore, our study aimed to propose a shortened version of the RMDQ by conducting confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), specifically on data from Korean RMDQ responses, which were provided by patients experiencing moderate to severe back pain. This analysis may help identify the most suitable structure for simplifying the questionnaire.

Introduction

- 2.1. Study design

- This secondary analysis aimed to investigate the structural validity of the RMDQ in patients with chronic LBP who underwent pharmacopuncture or physical therapy (PT). In this secondary analysis, we used two clinical studies: a pilot clinical study (unpublished, NCT04576520) involving 32 participants and a clinical study involving 100 participants (NCT048333309). Both studies were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine, Seoul, Korea (JASENG 2020-08-009, JASENG 2020-08-018, JASENG 2020-08-014, JASENG 2020-08-013, JASENG 2021-02-012, JASENG 2021-02-032, JASENG 2021-02-013, and JASENG 2021-02-014). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

- Comprehensive details on the full-scale randomized controlled trial (RCT) (NCT0483333009) can be found elsewhere [17,18]. In brief, the trials were two-arm, parallel, multicenter RCTs conducted at four Korean medicine hospitals. The participants were randomly assigned to undergo 10 sessions of either pharmacopuncture or PT over a 5-week period. The inclusion and exclusion criteria and measurement outcomes were similar between the groups. The pilot and the full-scale studies had a follow-up period of 16 and 25 weeks, respectively.

- The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) guidelines recommend that the sample size for factor analysis of health measurements should be at least five times the number of items for statistical adequacy [19]. Based on this criterion, the minimum sample size required for the RMDQ-24 was 120 participants. In the present study, we used baseline values of the RMDQ-24 from 132 patients who participated in the trial and received either pharmacopuncture (n = 66) or PT (n = 66).

- 2.2. Evaluation tools

- The RMDQ measures disability in individuals with LBP and consists of 24 items that describe situations experienced by people with LBP, with scores ranging from 0 to 24 points. We used the validated Korean version of the RMDQ-24 to measure disability in patients with chronic LBP who received integrative medical treatments [8].

- 2.3. Statistical analysis

- We performed a descriptive analysis to examine demographic and clinical variables. Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were presented as relative and absolute frequencies.

- We used CFA to identify the best structure of the RMDQ via R Studio software (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria), using the lavaan and semPlot packages, with the implementation of a tetrachoric matrix and the robust diagonally weighted least squares extraction method. We considered adequate values of fit indices for the following cut-off values: chi-squared/degree of freedom (dF) < 3, comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) > 0.85, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.9, and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) < 0.08.

- For the comparison between models, the structure with the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) values was considered more appropriate.

- The method of reducing the number of items of the RMDQ takes modification indices (MIs) into consideration, which indicates redundant items in pairs and factor loadings. We considered redundant items as those with MI > 10. In each paired analysis, the redundant items with the lowest factor loadings were excluded.

- We assessed criterion validity and considered the RMDQ-24 (long version) to be the gold standard. As the data did not present a normal distribution when analyzed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, the Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rho) was used to correlate the long and short versions. A correlation magnitude > 0.70 was considered the appropriate cut-off point for criterion validity.

2. Materials and Methods

- The study sample comprised 132 participants from the two original RCTs. Most participants were women (60.6%), and the mean age was 47.98 ± 12.13 years. All patients experienced moderate-to-severe pain (Table 1). The mean LBP intensity was 6.46 points and the mean radiating pain was 3.55 points on the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS). The mean RMDQ score was 14.59.

- Table 2 [12–14,20–22] lists the RMDQ structures tested, including the newly proposed model. Table 3 summarizes the MIs and factor loadings for each pair with an MI of 10 or higher. Forty decisions were made, which excluded 18 items. Table 4 [12–14,20–22] presents the six models tested in this study, including the original 24-item RMDQ. Using our data, the only model with a CFI ≥ 0.9, TLI ≥ 0.85, and RMSEA ≤ 0.09 was Model 7 (RMDQ-6), which is the model suggested in this study. Regarding criterion validity, the correlation between the 24- and 6-item RMDQ versions was adequate (rho = 0.884, p < 0.001). The RMDQ-6 (including the Korean version) is available in Supplementary Material 1 and 2, and its path diagram is presented in Fig. 1.

3. Results

- The analysis was conducted on 132 individuals using data from two clinical studies involving integrative medicine. The RMDQ-6 model met the criteria for adequate values of fit. However, it did not have the smallest values in terms of the AIC and BIC. The RMDQ-6 did not fit the relative indices with smallest values.

- As shown in Table 4, only the RMDQ-6 exhibited a CFI of 0.90 or higher, compared to models in other studies (RMDQ-11, RMDQ-15, RMDQ-16, and RMDQ-18). This discrepancy may arise from language differences or variations in the patient populations included in each study. Among the studies conducted thus far, Frota et al [16] targeted patients with LBP with NRS scores of 3 or higher, whereas our study focused on patients with an average NRS score of 6.47, which may account for the difference. Takara et al [20] targeted older adults, which differed from our study with an average age of 47.98 years. Williams and Myers [21] reported results for acute LBP, which could lead to differences due to variations in item responses or distribution, given the distinct prevalence periods between patients with acute and chronic LBP. Additionally, the differences might be attributed to the use of different language versions; Williams and Myers [21] and Stratford and Binkley [13] used the English version, whereas Takara et al [20] and Frota et al [16] used the Brazilian version. Various short versions of the RMDQ have been proposed; however, there are slight differences in the analytical methods employed. Stroud et al [14] proposed a method using the item response theory, whereas Frota et al [16] used a CFA similar to ours.

- The items included in both the RMDQ-6 and other simplified RMDQs published so far were identified as items 3 (walking more slowly) and 16 (trouble putting on socks). These items could be viewed as representative of the functioning of low back pain patients, regardless of cultural and linguistic differences. Additionally, RMDQ-6 included more items related to sleeping or lying down compared to other simplified RMDQ versions (item 6, lie down to rest more often; item 18, sleep less well; and item 14, difficulty turning over in bed). Further research in the future may be necessary to ascertain whether this characteristic is exclusive to severe patients or indicative of cultural differences.

- Our study performed an RMDQ analysis using clinical data; however, it had limitations with respect to the sample size used for factor analysis. The sample size may have been small compared to that of other studies [16]. However, some studies have suggested a minimum sample size of 100 individuals when conducting factor analyses using more than five factors [23]. In this context, our study exceeded this minimum threshold, and this could be considered an appropriate sample size [19]. Our proposed one-domain, 6-item model did not meet the fit index conditions we had set. Furthermore, this study only introduced a simplified version of the RMDQ-6, and further research is needed on its clinical applications, such as minimal clinically important differences and substantial clinical benefits.

- Since the studies conducted in English-speaking countries were in English and those in Brazil were in Portuguese, the generalizability of our findings may be limited owing to cultural differences. However, future research should explore the use of the RMDQ-6 in various languages to determine whether similar results can be obtained.

- Fewer items can make a questionnaire easier to administer. The RMDQ-6 has the fewest items among the proposed versions, making it highly suitable for clinical and research purposes. This facilitates the assessment of treatment efficacy in addressing back pain or measuring recurrence more quickly. Therefore, it can be widely used in clinical research. Future studies using the RMDQ-6 should explore aspects such as minimal clinically important differences and substantial clinical benefits. Additionally, our study may be more reliable than other studies because it used response data from clinical studies targeting patients with a demonstrated need for back pain treatment, based on their actual severity. Moreover, the RMDQ-6 demonstrated strong criterion validity, with a correlation of Rho = 0.884, thereby indicating a significant association with the full-length version.

4. Discussion

- The RMDQ-6 is a shortened version of the RMDQ instrument, developed using CFA, and it exhibited a significant correlation with the original RMDQ. Given its simplicity and validity, we expect that the RMDQ-6 can be widely used in future clinical studies.

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Material

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: YC and CHH. Methodology: YJL. Formal analysis: GCS. Investigation: GCS and CY. Writing original draft: YJL. Writing - review and editing: YCY and HCC.

-

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Funding

This study was funded by the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, Republic of Korea (grant no.: KSN1823211).

-

Ethical Statement

Both studies were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine, Seoul, Korea (JASENG 2020-08-009, JASENG 2020-08-018, JASENG 2020-08-014, JASENG 2020-08-013, JASENG 2021-02-012, JASENG 2021-02-032, JASENG 2021-02-013, and JASENG 2021-02-014).

Article information

Data Availability

| Items | 24 Items [12] | 18 Items [22] | 18 Items [13] | 11 Items [21] | 15 Items [14] | 16 Items [20] | 6 Items* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I stay at home most of the time because of my back | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 2. | I change position frequently to try and get my back comfortable | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 3. | I walk more slowly than usual because of my back | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4. | Because of my back, I am not doing any of the jobs that I usually do around the house | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 5. | Because of my back, I use a handrail to get upstairs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 6. | Because of my back, I lie down to rest more often | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 7. | Because of my back, I have to hold onto something to get out of an easy chair | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 8. | Because of my back, I try to get other people to do things for me | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 9. | I get dressed more slowly than usual because of my back | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 10. | I only stand up for short periods of time because of my back | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 11. | Because of my back, I try not to bend or kneel down | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 12. | I find it difficult to get out of a chair because of my back | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 13. | My back is painful almost all the time | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| 14. | I find it difficult to turn over in bed because of my back | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 15. | My appetite is not very good because of my back pain | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 16. | I have trouble putting on my socks (or stockings) because of the pain in my back | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 17. | I only walk short distances because of my back pain | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 18. | I sleep less well because of my back | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| 19. | Because of my back pain, I get dressed with help from someone else | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 20. | I sit down for most of the day because of my back | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 21. | I avoid heavy jobs around the house because of my back | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 22. | Because of my back pain, I am more irritable and bad tempered with people than usual | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| 23. | Because of my back, I go upstairs more slowly than usual | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 24. | I stay in bed most of the time because of my back | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Chi-squared/dF | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | AIC | BIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 [12] | 4.73 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.084 (0.079, 0.089) | 0.075 | 3,783.18 | 3,987.82 |

| Model 2 [22] | 4.61 | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.083 (0.076, 0.09) | 0.068 | 5,415.99 | 5,569.48 |

| Model 3 [13] | 4.74 | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.084 (0.078, 0.091) | 0.069 | 5,563.54 | 5,717.02 |

| Model 4 [21] | 6.34 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.101 (0.091, 0.111) | 0.073 | 4,656.78 | 4,759.10 |

| Model 5 [14] | 5.6 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.094 (0.086, 0.102) | 0.073 | 605.34 | 733.24 |

| Model 6 [20] | 5.68 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.094 (0.087, 0.102) | 0.076 | 3,034.83 | 3,171.26 |

| Model 7* | 4.75 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.084 (0.06, 0.111) | 0.044 | 2,683.32 | 2,734.48 |

- [1] Collaborators GLBP. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020 its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol 2023;5(6):e316−29.PubMedPMC

- [2] Dugan SA. The role of exercise in the prevention and management of acute low back pain. Clin Occup Environ Med 2006;5(3):615−32. vi−vii.PubMed

- [3] Krismer M, van Tulder M. Low back pain (non-specific). Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2007;21(1):77−91.ArticlePubMed

- [4] Hansen JAL, Fast T, Wangen KR. Productivity Loss Across Socioeconomic Groups Among Patients With Low Back Pain or Osteoarthritis: Estimates Using the Friction-Cost Approach in Norway. PharmacoEconomics 2023;41(9):1079−91.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [5] Fairbank J, Couper J, Davies JB, O’Brien JP. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy 1980;66(8):271−3.PubMed

- [6] Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983;8(2):141−4.PubMed

- [7] Stratford PW, Binkley JM, Riddle DL. Development and Initial Validation of the Back Pain Functional Scale. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(16):2095−102.ArticlePubMed

- [8] Lee JS, Lee DH, Suh KT, Kim JI, Lim JM, Goh TS. Validation of the Korean version of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. Eur Spine J 2011;20(12):2115−9.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [9] Küçükdeveci AA, Tennant A, Elhan AH, Niyazoglu H. Validation of the Turkish version of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire for use in low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26(24):2738−43.ArticlePubMed

- [10] Fan S, Hong H, Zhao F. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of simplified Chinese version of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37(10):875−80.ArticlePubMed

- [11] Exner V, Keel P. Measuring disability of patients with low-back pain-validation of a German version of the Roland & Morris disability questionnaire: Validierung einer deutschen Version des “Roland & Morris disability questionnaire” sowie verschiedener numerischer Ratingskalen. Der Schmerz 2000;14:392−400.PubMed

- [12] Nusbaum L, Natour J, Ferraz MB, Goldenberg J. Translation, adaptation and validation of the Roland-Morris questionnaire-Brazil Roland-Morris. Braz J Med Biol Res 2001;34:203−10.ArticlePubMed

- [13] Stratford PW, Binkley JM. Measurement properties of the RM-18: a modified version of the Roland-Morris Disability Scale. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22(20):2416−21.PubMed

- [14] Stroud MW, McKnight PE, Jensen MP. Assessment of self-reported physical activity in patients with chronic pain: development of an abbreviated Roland-Morris disability scale. J Pain 2004;5(5):257−63.ArticlePubMed

- [15] Friedman BW, Schechter CB, Mulvey L, Esses D, Bijur PE, John Gallagher E. Derivation of an Abbreviated Instrument For Use in Emergency Department Low Back Pain Research: The Five-item Roland Morris Questionnaire. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20(10):1013−21.ArticlePubMed

- [16] Frota NT, Fidelis-de-Paula-Gomes CA, Pontes-Silva A, Pinheiro JS, de Jesus SFC, Apahaza GHS, et al. 15-item Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ-15): structural and criterion validity on patients with chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022;23(1):978. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [17] Park KS, Kim C, Kim JW, Kim SD, Lee JY, Lee YJ, et al. A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial on the Effectiveness and Safety of Pharmacopuncture for Chronic Lower Back Pain. J Pain Res 2023;16:2697−712.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [18] Park KS, Kim S, Seo JY, Cho H, Lee JY, Lee YJ, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Pharmacopuncture Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Protocol for a Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pain Res 2022;15:2629−39.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [19] Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, Alonso J, Patrick DL, de Vet HCW, et al. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 2018;27(5):1147−57.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [20] Takara KS, Alamino Pereira, de Viveiro L, Moura PA, Marques Pasqual A, Pompeu JE. Roland-Morris disability questionnaire is bidimensional and has 16 items when applied to communitydwelling older adults with low back pain. Disabil Rehabil 2023;45(15):2526−32.ArticlePubMed

- [21] Williams R, Myers A. Support for a shortened Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire for patients with acute low back pain. Physiother Can 2001;53:60−6. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1572543025122549504.

- [22] Davidson M. Rasch Analysis of 24-, 18- and 11-item versions of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. Qual Life Res 2009;18:473−81.ArticlePubMedPDF

- [23] Gorsuch RL. Exploratory Factor Analysis. Edited by Nesselroade JR, Cattell RB: Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology. Boston (MA), Springer US, 1988, pp 231−58.Article

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite