Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Perspect Integr Med > Volume 2(1); 2023 > Article

-

Editorial

Integration of Acupuncture into UK Healthcare - A NICE Perspective: Why is Acupuncture Now Recommended for Chronic Pain but not for Back Pain or Osteoarthritis -

Mike Cummings*

-

Perspectives on Integrative Medicine 2023;2(1):3-7.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.56986/pim.2023.02.002

Published online: February 21, 2023

British Medical Acupuncture Society, London, UK

- *Corresponding author: Mike Cummings, British Medical Acupuncture Society, 60 Great Ormond Street, London, UK, E-mail: mike.cummings@btinternet.com

• Received: January 3, 2023 • Accepted: January 26, 2023

©2023 Jaseng Medical Foundation

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

- 2,033 Views

- 38 Download

- 1 Crossref

Abstract

- In April 2021, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published a guideline on chronic pain (NG193) with a recommendation to consider a single course of acupuncture treatment in patients with chronic primary pain. This positive recommendation came after the NICE guideline on low back pain and sciatica (NG59) announced in November 2016, that acupuncture treatment did not work for back pain, having previously recommended it in 2009 (CG88). This article attempts to explain this apparent contradiction in recommendations by tracing the history of acupuncture debates in the NICE guidelines over the last 2 decades.

- It was a couple of chance events early in my medical career that steered me to a career in acupuncture. The first was seeing that acupuncture was being used in the British military in the late 1980’s. The second was taking over a small private acupuncture practice from Dr. Adrian White in the mid 90’s, so that he could move into full time research.

- Adrian, who had originally taught me acupuncture, then encouraged me not to necessarily believe all that I had been taught at medical school, and to look for evidence in support of my conviction that acupuncture was a really good treatment for muscle pain [1]. This naturally led me into performing systematic reviews and peer reviewing research, and the results of my first systematic review led me to start questioning a lot of the orthodox medicine that I had naturally assumed to be true. Specifically, that injections of local anesthetics and corticosteroids for muscle pain were no different to injections of saline or water [2].

- By the mid 00’s I had been a journal editor, a peer reviewer, and a systematic review author for several years, so I was in an ideal position to take an interest in the first guideline from the then National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) that considered acupuncture [3], and every guideline since [4–10]. NICE has subsequently changed its name at least twice, and is now the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [11].

- I also took an interest in Cochrane reviews of acupuncture and was stimulated to read a whole review for the first time in 1999 [12], when its conclusion appeared to be completely at odds with the first meta-analysis of acupuncture for low back pain [13]. I discovered that the “no evidence” conclusion of Van Tulder et al was because reviewers disagreed on the interpretation of results from certain trials, one of which did not actually include any acupuncture [14]. I came away with the strong impression that somebody needed to keep an eye on them, and I took on the job.

- Later I had the experience of helping perform a Cochrane review of “Homeopathic medicines for adverse effects of cancer treatments” [15], and contributing as an advisor to a NICE guideline development group (GDG) for the management of low back pain [4], so I came to better appreciate the challenges of both, and I subsequently came to be somewhat less critical. That is not to say that I am uncritical, as the following narrative will demonstrate. We cannot really continue to allow data errors, orthodox biases, or conflicts of interest to influence national provision of heath care without at least raising a voice from time to time.

Introduction

- In 2004, we (the acupuncture research community) had a couple of relatively large, positive, sham-controlled trials of electroacupuncture (EA) in osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee [16,17]. I thought there was a possibility that we might get a positive recommendation from NICE for acupuncture treatment in OA before we got one for my favorite condition - muscle pain or myofascial pain. I suggested to Adrian that we should perform a systematic review with a meta-analysis on “Acupuncture treatment for chronic knee pain” [18]. Our review, which was published in 2007, demonstrated efficacy when compared with sham treatments, yet the subsequent NICE guideline for treatment of osteoarthritis (CG59) published in 2008, recommended against the use of EA [3]. This decision was based on health economic modelling using efficacy data from a single study with the term “electroacupuncture” in the title, even though other trials had also used EA. To make matters worse, I had just convinced colleagues at the Royal London Homeopathic Hospital, as it was then known (now the Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine), to set up group acupuncture clinics (to be as efficient as possible) to treat patients with knee OA with EA [19].

- Adrian and I argued that modelling cost-effectiveness based on the difference between real acupuncture and sham treatment (i.e. proper needling versus gentle needling) did not make sense [20], but the health economist responsible for the NICE guideline on osteoarthritis argued that it did [21]. Later, in 2012, he came to appreciate that this approach was problematic [22]. Fortunately, our group clinics at the Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine survived the negative recommendation for EA [19], but they eventually succumbed following the draft of the second low back pain guideline published in 2016 [7], which triggered widespread decommissioning of acupuncture services across the UK National Health Service (NHS), along with the rhetoric that “acupuncture is no better than a placebo for back pain” [23].

- With a more pragmatic cost-effectiveness perspective accepted, I thought group acupuncture clinics for OA were the solution to the problem, but the next time around the NICE guidelines introduced another hurdle - the dreaded minimal clinically important difference (MCID) [6]. The MCID chosen was a standard mean difference (SMD) of 0.5. This is a measure of effect size where the mean difference between an intervention and control is divided by the standard deviation of the difference. In an individual patient data meta-analysis of acupuncture for chronic pain [24], the SMD over no acupuncture controls was greater than 0.5 for acupuncture treatment of OA, but the SMD over sham treatment was less than 0.5. So, in the subsequent NICE guidance for the treatment of OA (CG177) published in February 2014, acupuncture treatment for OA sadly fell at the first explanatory hurdle [6].

- The guideline for the diagnosis and management of OA was updated again in 2022 (NG226), and a full cost-effectiveness analysis was performed for EA [10]. In some of the GDG analyses for NG226, EA was superior to sham acupuncture by an acceptable margin (i.e., SMD greater than 0.5), hence a full cost-effectiveness analysis was performed. However, due to inconsistency in the effect size of acupuncture treatment over sham acupuncture treatment and the potential financial cost of a positive recommendation by NICE to the UK NHS, the GDG did not make a positive recommendation for EA treatment of OA, and recommended against offering acupuncture or dry needling [25]. As in the past, the GDG recommended conventional approaches such as weight loss and exercise that are, in one rigorous analysis, inferior to acupuncture in terms of effectiveness in the relief of pain due to OA of the knee [26].

Acupuncture Treatment for Osteoarthritis

- Around the same time (2008) as I was reeling from the negative NICE recommendation for EA (my favorite treatment approach) in OA (CG59), I was invited to join a NICE GDG to advise on acupuncture treatment for low back pain. The scope of the guideline was low back pain in adults from 6 weeks to 1 year, so mainly aimed at treatment in primary care, and the chair of the GDG was an academic GP (involved in research, teaching and clinical work). The approach to the evidence was much more pragmatic than the approach which resulted in the CG59 guideline for treatment of OA, and in 2009 acupuncture was recommended for the treatment of low back pain along with exercise and manual therapies based on patient choice (CG88) [4]. What I did not see at the time was the reaction from a group of pain interventionists in secondary care who took exception to a recommendation against spinal injections in patients with pain for less than one year. They called an extraordinary meeting of the British Pain Society and put forward a vote of no confidence in the president, who had been a key member of the GDG. He subsequently resigned in 2009 [27].

- I understand that meetings then took place out of the public eye between the British Pain Society and NICE representatives before the announcement of a new updated guideline in 2016 (NG59). None of the key protagonists from CG88 were invited to the new GDG despite applying, and the scope of the guideline changed substantially. Sciatica was included, and time limitations were removed.

- Whilst we could see the writing on the wall based on the interests and opinions of several members of the GDG, it was still shocking to see a flagrant exhibition of double standards in the assessment of research evidence for conventional interventions compared with those applied to acupuncture treatment of low back pain and sciatica in the NG59 guideline [7,28].

- There was a conference presentation from the British Medical Acupuncture Society at the Spring Scientific Meeting in May 2017 that narrated the story of acupuncture recommendations in CG88 published in 2009 to NG59 published in 2016 [29], and this is freely accessible.

Acupuncture Treatment for Back Pain

- Having followed the large-scale clinical acupuncture trials performed in Germany in the 00’s [30] which went on to dominate the subsequent meta-analyses in terms of statistical power (larger trials get greater weighting in meta-analysis), and having seen the approach of the NICE guidelines for the treatment of OA, I was not expecting a positive recommendation for acupuncture in the headache guideline (CG150) [5]. Acupuncture works well in the treatment of headaches, but so does sham acupuncture, and the difference between treatments would be unlikely to meet a MCID of 0.5 if that were applied.

- However, my expectations were elevated when a neurologist from the GDG attended one of the British Medical Acupuncture Society foundation courses several months before the CG150 guideline was released. He said he had looked at the evidence and whilst it was not particularly convincing, the evidence for other interventions was equally unimpressive. I was pleased that he attended the entire course, and subsequently used acupuncture for a time in his neurology practice.

- When the guideline CG150 was released in 2012, the thing that shocked me was the confident statement that topiramate (an anti-epileptic drug that was the current preferred treatment in migraine prophylaxis) was twice as good as acupuncture. I had already seen one head to head comparison demonstrating the superiority of acupuncture [31], and a Cochrane review in 2016 subsequently confirmed a more general advantage of acupuncture over drug prophylaxis [32].

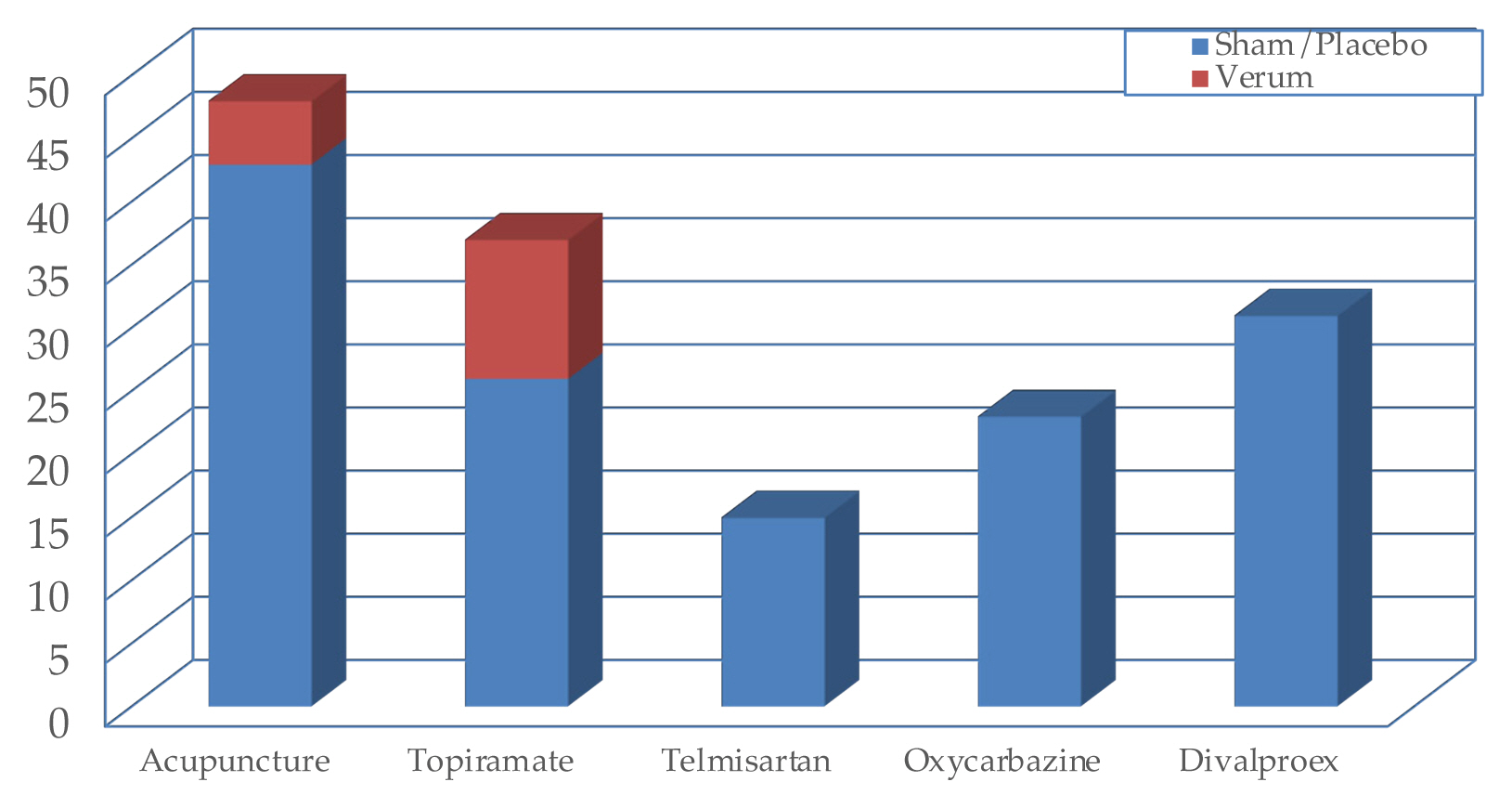

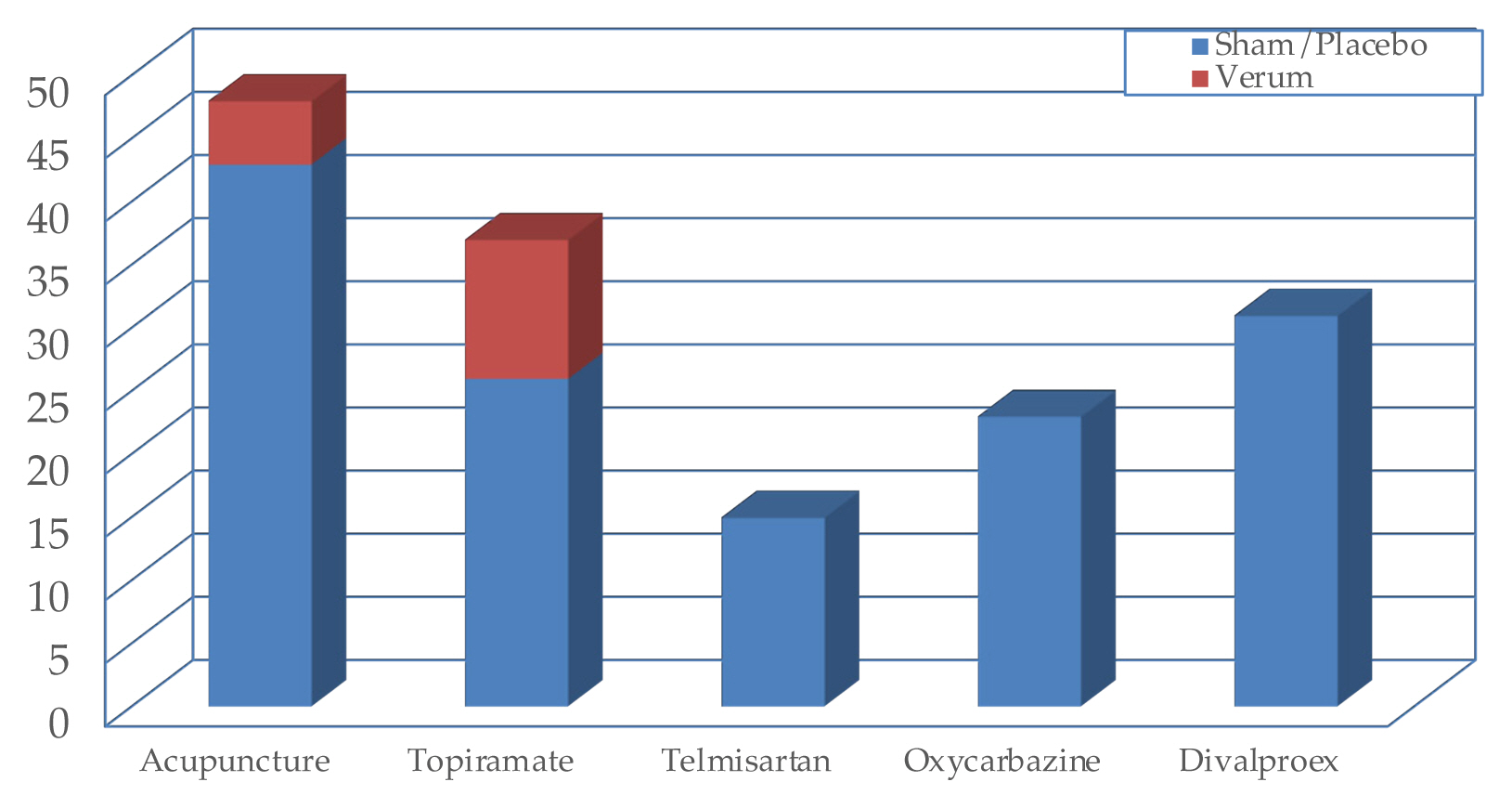

- This difference can be explained by the explanatory approach taken by the NICE GDG that only considered the effect of acupuncture in the control of migraines compared with sham acupuncture and comparing this difference with the difference between the effect of topiramate compared with placebo. The data used gave a responder rate for sham acupuncture which was higher than topiramate (Fig. 1), but this comparison was not used because it was considered not appropriate to compare different interventions directly when one (acupuncture) had a much larger placebo effect. This was the NICE GDG justification for placing data for sham acupuncture and placebo drugs into the same node of their limited network meta-analysis [5], something we argued strongly against [33]. Of course, we would say that sham acupuncture is not an inactive placebo [34], and subsequently in 2013, a rigorous meta-analysis of placebo and sham controls in migraine prophylaxis determined both sham acupuncture and sham surgery to be significantly more effective than all other controls [35].

Acupuncture Treatment for Headaches

- The most contemporary, positive guideline - a guideline on chronic primary pain [8,36] was published in April 2021 (NG193), and recommends acupuncture, albeit with financial limitations, to the provision in the UK NHS. Many groups representing NHS providers questioned why acupuncture was being recommended for chronic pain when it had not been recommended for back pain, which is probably the biggest cause of chronic pain in the community.

- Ironically, the reason why acupuncture was recommended for the treatment of chronic pain was because the trial data on acupuncture treatment of back pain was deliberately excluded by the GDG for NG193. This data involves two very large sham controlled trials in which the response rates were unexpectedly high in the sham acupuncture groups [37,38], thus reducing the group mean difference between real acupuncture and sham acupuncture when included in meta-analysis. By excluding these 2 trials on acupuncture treatment of chronic low back pain and leaving trials on neck pain, fibromyalgia, myofascial pain, and chronic pelvic pain, the group mean difference exceeded the pre-defined SMD of 0.5 for the MCID.

- Unlike the NG59 guideline for low back pain and sciatica, the GDG was not prepared to set a double standard and insisted on recommending acupuncture despite pressure to do otherwise from the hierarchy (personal communications with unnamed sources). They also recommended against the use of drugs that are still in very common use in the treatment of chronic pain including the gabapentinoids, opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, and paracetamol.

- Interestingly, the GDG left the door open to treating chronic low back pain as well by including the proviso that you first follow guideline NG59, which recommends against acupuncture, but if the pain or its impact is out of proportion to the underlying condition and would be better managed as chronic primary pain, then acupuncture becomes one of the options to consider.

Acupuncture Treatment for Chronic Primary Pain

- Published in August 2021, guideline NG201 considered acupuncture for the treatment of pelvic girdle pain, but the GDG agreed that the evidence was mixed and of poor quality. They did not recommend acupuncture for this intervention. They did recommend that acupressure could be considered for women with moderate-to-severe nausea and vomiting as an additional antenatal treatment.

Acupuncture Treatment Within Antenatal Care

- After many years of scrutinizing meta-analyses and guidelines, as well as manuals of methodology, I have finally come to terms with the reasons behind the sometimes bizarre and often opposing recommendations, conclusions, and rhetoric concerning the use of acupuncture treatment. The difference usually stems from whether the commentator takes an explanatory point of view (acupuncture versus sham acupuncture/robust needling versus gentle needling) or a pragmatic point of view (acupuncture versus no acupuncture/acupuncture versus other treatments).

- If you want the bottom line in big acupuncture data, the place to go is the individual patient data meta-analysis (IPDM) led by Andrew Vickers and including a large group of researchers collectively known as the Acupuncture Trialists Collaboration. They published the first version of their IPDM in 2012, after considerable difficulty [24,39], and an update of the IPDM was published in 2018 [40]. Interestingly, after comments on the draft guideline for NG59, data from the IPDM was included in the final version, but the data analysts, in error, used SMD data from the IPDM paper in their own meta-analysis of mean differences. This error made the summary value of acupuncture versus sham acupuncture look even worse than in the draft guideline for NG59, and the GDG over interpreted this error by suggesting that the better the quality of data the smaller the effect of acupuncture. Once a guideline is published there is no chance for further comment, even if the errors are as gross as using SMD instead of MD.

- I continue to push for a fair and sensible review of the evidence by NICE GDGs and Cochrane to support the use of acupuncture treatment; however, Cochrane appears to be moving away from the more pragmatic view of the data [32], to a more rigid explanatory one, as illustrated by the long-awaited update to the low back pain review [41].

- For a summary of the NICE guidelines that have considered acupuncture and the outcomes of those guidelines regarding acupuncture recommendations, see Table 1.

Conclusion

-

Conflicts of Interest

None.

-

Ethical Statement

This research did not involve any human or animal experiments.

-

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

-

Funding

None.

Article information

Fig. 1

Responder rate based on a reduction in days with migraine of 50% or greater.

Responder rates based on a reduction in days with migraine of 50% or greater in migraine prophylaxis treatments for real (red) and sham (blue) acupuncture, and real (red) topiramate and placebo (blue) topiramate, and placebo (blue) in trials of other drugs. Data taken from a limited network meta-analysis performed to recommend the guidelines for acupuncture treatment of headaches CG150, where sham acupuncture was assumed to be equivalent to a drug placebo. The CG150 guideline development group concluded that topiramate was twice as good as acupuncture in the treatment of headaches, yet the data used for sham acupuncture exceed that used for real topiramate.

Table 1NICE guidelines that have considered acupuncture.

| No. | Topic | Date published |

|---|---|---|

| CG55 | Osteoarthritis* | February 2008 |

| CG88 | Low back pain† | May 2009 |

| CG150 | Headache† |

September 2012 August 2015 (addendum to the guidelines) |

| CG177 | Osteoarthritis* | February 2014 |

| NG59 | Low back pain & sciatica* | November 2016 |

| NG193 | Chronic pain† | April 2021 |

| NG201 | Antenatal care* | August 2021 |

| NG226 | Osteoarthritis* | October 2022 |

- [1] Cummings TM. A Computerised Audit of Acupuncture in Two Populations: Civilian and Forces. Acupunct Med 1996;14(1):37−9.ArticlePDF

- [2] Cummings TM, White AR. Needling therapies in the management of myofascial trigger point pain: A systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82(7):986−92.ArticlePubMed

- [3] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. Osteoarthritis: The care and management of osteoarthritis in adults. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: 2008 [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg59

- [4] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. Low back pain in adults: Early management: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: 2009 [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG88

- [5] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. Overview: Headaches in over 12s: Diagnosis and management: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: 2012 [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG150

- [6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. Osteoarthritis: Care and management: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: 2014 [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG177

- [7] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. Overview: Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: Assessment and management: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: 2016 [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG59

- [8] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. Overview: Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: Assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 9]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG193

- [9] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. Overview: Antenatal care: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: 2021 [cited 2022 Dec 26]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG201

- [10] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. Overview: Osteoarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG226

- [11] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: [cited 2022 Dec 26]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/

- [12] van Tulder M, Cherkin D, Berman B, Lao L, Koes B. Acupuncture for low-back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester (UK), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 1999.Article

- [13] Ernst E, White AR. Acupuncture for back pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 1998;158(20):2235−41.ArticlePubMed

- [14] Garvey TA, Marks MR, Wiesel SW. A prospective, randomized, double-blind evaluation of trigger-point injection therapy for low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989;14(9):962−4.ArticlePubMed

- [15] Kassab S, Cummings M, Berkovitz S, van Haselen R, Fisher P. Homeopathic medicines for adverse effects of cancer treatments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD004845.. ArticlePubMedPMC

- [16] Berman BM, Lao L, Langenberg P, Lee WL, Gilpin AMK, Hochberg MC. Effectiveness of Acupuncture as Adjunctive Therapy in Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Ann Intern Med 2004;141(12):901−10.ArticlePubMed

- [17] Vas J, Méndez C, Perea-Milla E, Vega E, Panadero MD, León JM, et al. Acupuncture as a complementary therapy to the pharmacological treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2004;329(7476):1216. ArticlePubMedPMC

- [18] White A, Foster NE, Cummings M, Barlas P. Acupuncture treatment for chronic knee pain: A systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(3):384−90.ArticlePubMed

- [19] Berkovitz S, Cummings M, Perrin C, Ito R. High Volume Acupuncture Clinic (Hvac) for Chronic Knee Pain - Audit of a Possible Model for Delivery of Acupuncture in the National Health Service. Acupunct Med 2008;26(1):46−50.ArticlePubMedPDF

- [20] White A. NICE guideline on osteoarthritis: Is it fair to acupuncture? No. Acupunct Med 2009;27(2):70−2.Article

- [21] Latimer N. NICE guideline on osteoarthritis: Is it fair to acupuncture? Yes. Acupunct Med 2009;27(2):72−5.Article

- [22] Latimer NR, Bhanu AC, Whitehurst DGT. Inconsistencies in NICE guidance for acupuncture: Reanalysis and discussion. Acupunct Med 2012;30(3):182−6.ArticlePubMedPDF

- [23] Davis N. [Internet] Acupuncture for low back pain no longer recommended for NHS patients. The Guardian: [cited 2022 Dec 26]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/mar/24/acupuncture-for-low-back-pain-no-longer-recommended-for-nhs-patients

- [24] Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster NE, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: Individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2012;172(19):1444−53.ArticlePubMedPMC

- [25] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. Recommendations: Osteoarthritis in over 16s: Diagnosis and management: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng226/chapter/Recommendations

- [26] Corbett MS, Rice SJC, Madurasinghe V, Slack R, Fayter DA, Harden M, et al. Acupuncture and other physical treatments for the relief of pain due to osteoarthritis of the knee: Network meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21(9):1290−8.ArticlePubMedPMC

- [27] Kmietowicz Z. President of British Pain Society is forced from office after refusing to denounce. NICE guidance on low back pain. BMJ 2009;339:b3049. Article

- [28] Cummings M. Rapid response to: Low back pain and sciatica: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2017;356:i6748. PubMed

- [29] BMAS website [Internet]. Acupuncture in Low Back Pain: [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.medical-acupuncture.co.uk/Professionals/AcupunctureinLowBackPain.aspx

- [30] Cummings M. Modellvorhaben Akupunktur-A summary of the ART, ARC and GERAC trials. Acupunct Med 2009;27(1):26−30.ArticlePubMedPDF

- [31] Yang CP, Chang MH, Liu PE, Li TC, Hsieh CL, Hwang KL, et al. Acupuncture versus topiramate in chronic migraine prophylaxis: A randomized clinical trial. Cephalalgia 2011;31(15):1510−21.ArticlePubMedPDF

- [32] Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, Fei Y, Mehring M, Vertosick EA, et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2016(6):CD001218. ArticlePubMedPMC

- [33] White A, Cummings M. Inconsistent placebo effects in NICE ’s network analysis. Acupunct Med 2012;30(4):364−5.ArticlePubMedPDF

- [34] White A, Cummings M. Does acupuncture relieve pain? BMJ 2009;338:a2760.. ArticlePubMed

- [35] Meissner K, Fässler M, Rücker G, Kleijnen J, Hróbjartsson A, Schneider A, et al. Differential effectiveness of placebo treatments: A systematic review of migraine prophylaxis. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(21):1941−51.ArticlePubMed

- [36] Kmietowicz Z. Offer exercise, therapy, acupuncture, or antidepressants for chronic primary pain, says NICE. BMJ. 2021, 373:p n907.. ArticlePubMed

- [37] Meissner K, Fässler M, Rücker G, Kleijnen J, Hróbjartsson A, Schneider A, et al. German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: Randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups. Arch Intern Med 2007;167(17):1892−8.ArticlePubMed

- [38] Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Avins AL, Erro JH, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, et al. A Randomized Trial Comparing Acupuncture, Simulated Acupuncture, and Usual Care for Chronic Low Back Pain. Arch Intern Med 2009;169(9):858−66.ArticlePubMedPMC

- [39] Vickers AJ, Maschino AC, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Sherman KJ, Witt CM; Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration. Responses to the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. Acupunct Med 2013;31(1):98−100.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- [40] Vickers AJ, Vertosick EA, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster NE, Sherman KJ, et al. Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Update of an Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. J Pain 2018;19(5):455−74.ArticlePubMedPMC

- [41] Mu J, Furlan AD, Lam WY, Hsu MY, Ning Z, Lao L. Acupuncture for chronic nonspecific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;12(12):CD013814. ArticlePubMedPMC

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- A Review of Key Research and Engagement in 2022

John McDonald, Sandro Graca, Claudia Citkovitz, Lisa Taylor-Swanson

Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine.2023; 29(8): 455. CrossRef

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite